Why Do Snakes Bask?

Snakes, like other reptiles, are cold-blooded – they are unable to internally regulate their body temperature. On cool days If their body temperature is low, they are sluggish. They don’t move quickly, don’t hunt effectively and if they have food in their stomachs, digestion comes to nearly a standstill.

They avoid this situation by basking when cool weather sets in. They lay in the sunshine and/or on rocks or substrate that is heated by the sun, and warm up. When they get to an optimal temperature, they can be active, hunt and digest the food they eat. During these shorter, cooler fall days, before snakes enter hibernation, a great deal of time is spent basking.

There is an advantage to using sunlight to control body temperature. Warm-blooded animals must eat a large amount of food fairly continuously because it is the digestion of the food that regulates their body temperature and produces heat, which they must maintain in order to survive. Cold-blooded animals don’t have this restriction since their body temperature is controlled externally. This is why a snake can go for a relatively long period of time (months, depending on species) without eating after it has consumed food. (Photo: Common Gartersnake peering out from under leaves after its basking was disturbed)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Purple Finches Irrupting

Every year a Winter Finch Forecast (https://finchnetwork.org/winter-finch-forecast-2022-2023 ) is published which predicts which finches in the northern boreal forests might be extending their range south due to a poor food supply farther north. These larger-than-normal movements of birds are referred to as irruptions, and they happen every year, to varying degrees with varying species.

This year’s Winter Finch Forecast predicted that Purple Finches would irrupt southward, following the large spruce budworm outbreak (producing short-term population increases) and poor mast crop in much of the eastern boreal forest. The past few days have proven the forecast right and signaled the start to a large-scale irruption event. Once Black Bears have gone into hibernation and your feeders are up, keep an eye out for ever-increasing numbers of Purple Finches (as well as irrupting Evening Grosbeaks).

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Bumble Bee Mouth Parts

Most bumble bees, except for the young queens, have only a few weeks left to live, but until a killing frost arrives, they will be gathering pollen and nectar for themselves and their colony. The various mouth parts that enable them to collect food are hidden behind the large lip that you see when you face a bumble bee head on.

Behind this lip, there are multiple structures that are adapted to grasp, shape and collect food. These include jaws, or mandibles, which clasp pollen and wax used to form cells for eggs. Under the mandibles are two long sheaths that also grasp and shape food called maxillae. Two labial palps located under the maxillae serve as taste sensors. Both of these structures, the maxillae and palps, form a horny sheath which protects the bee’s tongue.

Nectar is accessed with a proboscis which is basically a tube that is protected by the mandible, maxillae and labial palps. A tongue-like structure called a glossa protrudes from the proboscis. Its hairy tip is well suited for collecting nectar.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Wild Clematis Fruiting

Wild Clematis (Clematis virginiana), also known as Virgin’s Bower and Old Man’s Beard, is one of our native vines. It is a member of the buttercup family and bears clusters of white to green flowers that mature into fluffy seedheads. Ellen Rathbone in the Adirondack Almanack delightfully refers to these seed clusters as “Truffula Trees” — if you’ve ever rad The Lorax by Dr. Seuss, you can appreciate how apt this comparison is.

Wild Clematis contains glycosides and is toxic, so shouldn’t be consumed, but it is a very dramatic sight to come across when the seeds are mature and have yet to be dispersed.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Beavers Repairing and Reinforcing Lodges and Dams

Late October and early November is the busiest time of year for beavers. Their entire winter’s food supply must be cut, gathered, transported and piled next to their lodge so that they will have access to it under the ice. Mud, sticks, wads of grass and stones are collected to reinforce the lodge’s thick walls against the cold as well as coyotes and other predators. And dams, the structures which create ponds, must be patched and strengthened to withstand the rigors of winter.

The importance of maintaining a dam in good condition cannot be overstated, for without it, the pond would cease to exist, and no pond means no beavers. As Dietland Muller-Schwarze and Lixing Sun state in the Beaver, a beaver pond is a “highway, canal, escape route, hiding place, vegetable garden, food storage facility, refrigerator/freezer, water storage tank, bathtub, swimming pool and water toilet.” (They defecate only in water.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

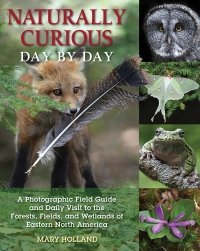

2023 Naturally Curious Calendar Orders Accepted Until Nov. 10

If you’re in need of holiday presents, or simply wish to gaze upon birds and beasts yourself throughout 2023, you might want to consider the gift of a 2023 Naturally Curious Calendar.

Orders can be placed by writing to me at 505 Wake Robin Drive, Shelburne, VT 05482. The calendars are printed on heavy card stock and measure 11” x 17” when hanging. There is one full-page photograph per month. The calendars are $35.00 each (includes postage). Please specify the number of calendars you would like to order, the mailing address to which they should be sent and your email address (so I can easily let you know I received your order and can quickly contact you if I have any questions). Your check can be made out to Mary Holland. You will receive your calendars within 1-3 weeks of placing an order.

Guaranteed orders can be placed starting today up until November 10th. Orders placed after November 10 will be filled as long as my supply of extra calendars lasts. (I have had so many last-minute requests (after the deadline) in past years that I have not been able to fill all of the orders, so if you want to be sure of having your order filled, I encourage you to place your order before November 10th. I hate to disappoint anyone.)

Monthly photos: Cover-moose; January-horned lark; February-barred owl impression in snow; March-beaver; April-great horned owls; May-showy lady’s slipper; June-black-crowned night heron; July-hummingbird clearwing moth; August-gray treefrog; September-red-eyed vireo; October-porcupine; November-wild turkey; December-black-capped chickadee.

Galium Sphinx Moth Larvae Pupating

Some of the largest moths in the world belong to the hawk, or sphinx, moth family. As larvae, most hawk moths have a “horn” at the end of their body. One of the most familiar hawk moth caterpillars is the Tobacco Hornworm, found on tomato plants. Most species produce several generations a summer, pupating underground and emerging after two or three weeks. One exception is the Galium Sphinx Moth (Hyles gallii) pictured, which usually has only one generation a year. In the fall the larvae, or caterpillars, work their way underground where they overwinter as pupae inside cocoons in a shallow burrow, emerging as adult moths next spring.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

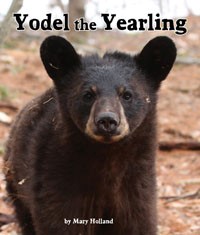

Black Bears Experiencing Hyperphagia

At the risk of boring NC readers who have been subscribers for six or more years, I am reposting both a photograph and narrative from a 2016 post that remains one of the most memorable animal signs I have ever come upon.

Black Bears are omnivores as well as opportunists. They will eat almost anything that they can find, but the majority of their diet consists of grasses, roots, berries, nuts and insects (particularly the larvae). As the days cool, and the time for hibernation approaches, Black Bears enter a stage called “hyperphagia,” which literally means “excessive eating.” They forage practically non-stop — up to 20 hours a day, building up fat reserves for hibernation, increasing their body weight up to 100% in some extreme cases. Their daily food intake goes from 8,000 to 15-20,000 calories. Occasionally their eyes are bigger than their stomachs, and all that they’ve eaten comes back up. Pictured is the aftermath of a Black Bear’s orgy in a cornfield.

If you share a Black Bear’s territory, be forewarned that they have excellent memories, especially for food sources. Be sure not to leave food scraps or pet food outside and either delay feeding birds until bears are hibernating (late December would be safe most years) or take your feeders in at night.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Yellow Orange Fly Agarics Fruiting

The Yellow Orange Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria var. formosa) is common in New England, especially where conifers grow. Out West this mushroom is often a bright red color, but in the East it’s typically orange/yellow.

When certain gilled mushrooms, including many Amanita species, first form they are encased in a membrane called a “universal veil.” As the mushroom enlarges and matures, the veil ruptures, with remnants of it remaining on the mushroom’s cap. Fly Agaric fungi got their name from the custom of placing little pieces of the mushroom in milk to attract flies. The flies supposedly become inebriated and crash into walls and die. This mushroom is somewhat poisonous (as are many Amanita species) and hallucinogenic when consumed by humans. The toxins affect the part of the brain that is responsible for fear, turning off the fear emotion. Vikings, who had a reputation for fierceness, are said to have ingested this mushroom prior to invading a village.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

What Other Naturally Curious People Are Saying