Whirligig Beetles Active

Congratulations to Stein Feick, the first person to correctly identify the Mystery Photo as a Whirligig Beetle! You usually see this aquatic beetle swimming around and around in circles on the surface of a pond searching for prey. A unique feature of most beetles in this genus is their divided eyes. Each eye is completely separated into two portions (see photo). One portion (dorsal) is above the water line and the other (ventral) is beneath the water on each side of their head, allowing them to see both in the air/on the surface of the water as well as under the water. The dorsal eyes have a limited field of view, so these beetles rest one of their antennae on the surface of the water to help them detect any motion caused by prey.

Congratulations to Stein Feick, the first person to correctly identify the Mystery Photo as a Whirligig Beetle! You usually see this aquatic beetle swimming around and around in circles on the surface of a pond searching for prey. A unique feature of most beetles in this genus is their divided eyes. Each eye is completely separated into two portions (see photo). One portion (dorsal) is above the water line and the other (ventral) is beneath the water on each side of their head, allowing them to see both in the air/on the surface of the water as well as under the water. The dorsal eyes have a limited field of view, so these beetles rest one of their antennae on the surface of the water to help them detect any motion caused by prey.

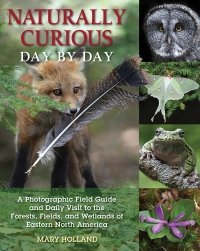

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Eastern Dobsonflies Emerging

Eastern Dobsonfly (Corydalus cornutus) larvae, known as Hellgramites, are the top invertebrate predators in the rocky streams where they occur. In this stage they look like underwater centipedes and consume tadpoles, small fish, and other young aquatic larvae. Adults keep watch over them from a nearby area above the water.

After leaving their stream and pupating on land, the 4”-5 ½”-winged adults, referred to as Eastern Dobsonflies, emerge. Males can easily be distinguished from females by their large, sickled-shaped mandibles which the females lack. (The short, powerful mandibles of the female are capable of giving a painful bite, which the males’ mandibles are not.) Adults are primarily nocturnal and they do not eat. During their short lifespan (about three days for males, eight to ten days for females) they concentrate on reproducing.

The elongated jaws of the male are used both as part of the premating ritual (males place their mandibles on the wings of the females) and as weapons for fighting rival males. (Thanks to Clyde Jenne for photo op.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to https://naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Broad-shouldered Water Striders Still Active

If you see what look like miniature water striders skating on the surface of a stream or pond, you may have come upon an aggregation of Broad-shouldered Water Striders, a different family of water striders from the ones we commonly see. They are tiny (2-6 mm) and very fast-moving, zipping here and there with the speed of a bullet, staying on top of the surface film, or surface tension, that is created by the attraction of water molecules. Adaptations to this mode of travel include non-wettable hairs at the ends of their legs that don’t disrupt the surface tension, and claws that are located a short distance up the outermost section of their legs rather than at the end of their legs, so as not to break this film.

Broad-shouldered Water Striders are often found in the more protected areas of a stream, where they tend to congregate in large numbers. Members of a common genus, Rhagovelia, are known as “riffle bugs” and are often found below rocks that are in the current. Broad-shouldered Water Striders locate their prey (water fleas, mosquito eggs and larvae, etc.) by detecting surface waves with vibration sensors in their legs. There can be up to six generations a summer (photo shows that they are still mating at the end of October). Broad-shouldered Water Striders spend the winter hibernating as adults, gathering in debris at the edge of the water or beneath undercut banks.

Crane Fly Larvae

A favorite past-time of mine is peering under logs and rocks to see what might be living there. (The logs and rocks are carefully replaced in the position in which they were found so as not to disturb the inhabitants any more than is necessary.) Recently I discovered a Crane Fly larva under a rock that was adjacent to a stream – a typical spot in which to find a soon-to-pupate larva. Roughly an inch long, the most distinguishing features are the ridges along its body, and the star-like appendages at the tip of its abdomen. If you examine the appendages closely, you will find two spiracles, through which the Crane Fly larva breathes, located in a recessed area in the center. Although you can’t see a head, it has one that is tucked into its thorax.

A favorite past-time of mine is peering under logs and rocks to see what might be living there. (The logs and rocks are carefully replaced in the position in which they were found so as not to disturb the inhabitants any more than is necessary.) Recently I discovered a Crane Fly larva under a rock that was adjacent to a stream – a typical spot in which to find a soon-to-pupate larva. Roughly an inch long, the most distinguishing features are the ridges along its body, and the star-like appendages at the tip of its abdomen. If you examine the appendages closely, you will find two spiracles, through which the Crane Fly larva breathes, located in a recessed area in the center. Although you can’t see a head, it has one that is tucked into its thorax.

The Crane Fly family is the largest family of true flies, in terms of number of species. They can be found in aquatic, semi-aquatic and terrestrial habitats. True flies do not have segmented legs that they can use to hold on to the substrate when they catch their prey. Many Crane Fly larvae feed on decomposing leaves, but those species of Crane Flies which are predators are capable of forming a large knot with the muscles at the end of their abdomen. When they catch prey with their mouthparts, they enlarge the end of their abdomen and wedge the knot between stones in order to anchor themselves.

What Other Naturally Curious People Are Saying