Black-capped Chickadees Nest-building

Spring is here and nest building has begun for many of our cavity nesters. Protected from the wind and low temperatures that can occur this time of year, birds that nest in cavities get a jump start on starting a family. Black-capped Chickadees typically seek out trees with punky wood that is soft enough for their small beaks to excavate. Birch, aspen and sugar maple are chosen with regularity.

While the nest site is often chosen by the female, both male and female chickadees participate in the excavation of the cavity. They take turns disappearing inside the hole (that they have created or one that a previous nesting woodpecker made or a natural cavity) and chipping away at its interior and then exit with a beak full of wood chips. Unlike many cavity nesters that just drop the chips to the ground from the hole, chickadees usually fly a short distance away before dropping them.

The female alone builds the nest inside the cavity. She usually uses coarse material such as moss for the foundation, and lines the nest with finer material such as rabbit fur and deer hair. Within one to two days of finishing the nest, she lays anywhere from one to thirteen eggs.

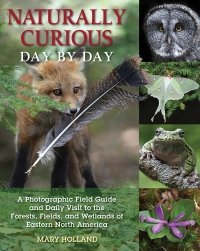

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Save Those Seedheads!

People have Echinacea (Coneflower) in their medicine cabinets for a number of reasons. One of the more prevalent ones is Echinacea’s purported ability to shorten the duration of the common cold and flu, as well as lessen the severity of symptoms. It wouldn’t be surprising to learn that humans learned of the possible benefits of this plant by observing the presence of butterflies (fritillaries, monarchs, painted ladies and swallowtails) at its flowers and birds (American Goldfinch, Black-Capped Chickadee, Dark-Eyed Junco, Downy Woodpecker, Northern Cardinal, Pine Siskin) at its seedheads.

This is the time of year gardeners are starting to think about cutting back their dying perennials in an effort to have tidier gardens. If you have Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) or one of the other species of Echinacea you know that they are no longer attracting the myriad butterflies that visit in the summer. However, hold your clippers, for it’s highly likely that birds, especially American Goldfinches, will be feeding on your coneflower seeds in the near future. These seedheads are beneficial not only because they provide seeds, but because they reduce the birds’ reliance on feeders in the winter. Finches are highly susceptible to Finch Eye Disease which spreads easily from infected birds to other finches when they all use the same feeder.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

An Ingenious Recycler

Recycling is the process of converting waste materials into new materials and objects. In the natural world, agents such as fungi and bacteria that turn dead plant and animal matter into air, water and nutrients come to mind. If you broaden the definition of recycling to include the re-use of material, however, many more organisms come into play.

Recycling is the process of converting waste materials into new materials and objects. In the natural world, agents such as fungi and bacteria that turn dead plant and animal matter into air, water and nutrients come to mind. If you broaden the definition of recycling to include the re-use of material, however, many more organisms come into play.

Some humans continue to feed birds in the spring after Black Bears have emerged from their dens. The bears have not eaten for four or five months and once their digestive system adjusts, they are extremely hungry. Available bird feeders are often raided by hungry bears at this time of year, and end up discarded on the forest floor with the seeds they contained ending up inside the bears’ stomachs. Eventually the bears defecate and their feces contain little else but the husks of sunflower seeds interspersed with intact seeds. Keen-eyed Black-capped Chickadees are very quick to take advantage of these recycled sources of protein. (Check the Chickadee’s beak closely.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Black-capped Chickadees Singing Their Spring Song

Would it surprise you to learn that Black-capped Chickadees have at least 16 different vocalizations? The two most common are its “chick-a-dee” call and its “fee-bee” song. The “chick-a-dee” vocalization for which these birds are named is sung by both sexes throughout the year, but it’s especially common in fall and winter. This call is used to convey a number of different messages. It’s given when a bird is separated from its mate or flock, when chickadees are mobbing a predator (lots of dee notes), to notify others when a predator has left, and when a new food source is discovered.

Would it surprise you to learn that Black-capped Chickadees have at least 16 different vocalizations? The two most common are its “chick-a-dee” call and its “fee-bee” song. The “chick-a-dee” vocalization for which these birds are named is sung by both sexes throughout the year, but it’s especially common in fall and winter. This call is used to convey a number of different messages. It’s given when a bird is separated from its mate or flock, when chickadees are mobbing a predator (lots of dee notes), to notify others when a predator has left, and when a new food source is discovered.

The two-noted, whistled “fee-bee” vocalization is given mostly by males, although not exclusively. While it can be heard throughout the year, this song is most common in late winter and spring and thus is referred to as the chickadee’s spring song. When chickadees are singing their “fee-bee” song, they are advertising their territories and attempting to attract mates.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Where Are All The Birds?

Even though signs as well as sightings of active bears are plentiful, and black-oiled sunflower seeds are an open invitation for them to visit and potentially become “nuisance” bears, many devoted bird-lovers have already hung out feeders in hopes of luring feathered friends closer to their home. Throughout northern New England so few birds have been attracted to these feeders that they have remained full, some not having been refilled since September. Our usual fall and winter visitors appear to have all but vanished, and concern has been growing amongst those who feed birds.

Those familiar with bird feeding habits know that in the fall, when seeds are abundant, feeder visits by resident birds typically slow down. However, this year, at least anecdotally, appears to be extreme in this regard. Warm weather extending into November certainly has lessened birds’ food requirements. But having sunflower seeds sprout in your feeder before the need to replenish them arrives is unusual, if not alarming.

Dr. Pam Hunt, Senior Biologist in Avian Conservation at New Hampshire Audubon, recently shared some of her personal research with the birding world (UV- Birders). Hunt has conducted a weekly, 10 km-long, bird survey near Concord, NH for the past 13 years. In addressing the current concern over a lack of feeder birds, she extracted the data she had accumulated on 12 common birds (Mourning Dove, Downy Woodpecker, Hairy Woodpecker, Blue Jay, Black-capped Chickadee, Tufted Titmouse, White-breasted Nuthatch, White-throated Sparrow, Dark-eyed Junco, Northern Cardinal, House Finch, American Goldfinch) over the last 13 falls, focusing on the period between Oct 1 and Nov 15. After extensive analysis, Hunt concluded that there has not been a dramatic decline in the number of birds this year, relative to the averages of the past 13 years. One cannot argue with scientific evidence (except for, perhaps, #45), but it does seem mighty quiet on the western (northeastern?) front this year.

Woodland Recycler

The ability to find food is crucial for all creatures. It involves looking in every potential location, including the waste material of other animals. Nothing goes to waste in the natural world, and I was fortunate to observe an example of this recycling phenomenon recently in bear-inhabited woodlands.

The ability to find food is crucial for all creatures. It involves looking in every potential location, including the waste material of other animals. Nothing goes to waste in the natural world, and I was fortunate to observe an example of this recycling phenomenon recently in bear-inhabited woodlands.

Even though feeding birds is discouraged at this time of year due to the seeds’ appeal to hungry, emerging Black Bears, many find it a hard habit to stop. Inevitably Black Bears will smell the seeds in feeders and help themselves to them. If this continues long enough, the bears will become habituated and eventually this can lead to their being considered a nuisance, which can lead to their demise. Thus, it’s best to stop feeding birds now that Black Bears have emerged from hibernation.

That said, those who continue to fill feeders in the spring and have had them raided by bears need not fear that their birds are without recourse should they find the feeders empty or missing. Much of what goes in comes out, and bears deposit their seed-laden scat throughout the woods, creating ground “feeders” for all kinds of creatures. In this instance, a Black-capped Chickadee repeatedly helped itself to uncracked sunflower seeds amongst a great deal of millet and sunflower seed husks in the scat of a Black Bear.

This post is dedicated to Sadie Brown, Solid Waste & Recycling Coordinator for the town of Melrose, MA.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Black-capped Chickadees Starting to Build Nests

At least two to four weeks before one would expect to find a black-capped chickadee building a nest, one was busily collecting hairs shed by my chocolate lab yesterday. In addition to fur, chickadees line their nest with grass (not available yet here), down and moss (hard to come by with two feet of snow still on the ground). Chickadees are able to nest this early in part because they nest in cavities, which offer them protection from the elements. Not having bills strong enough to hammer out cavities in living trees, chickadees rely heavily on rotting stumps for nest sites — the wood in them is punky and easy to remove. Birch, poplar and sugar maple snags and stumps are preferred nesting trees. If you want to provide chickadees and other birds with nesting material, take advantage of the fact that dogs and cats are shedding now, and recycle their fur.

At least two to four weeks before one would expect to find a black-capped chickadee building a nest, one was busily collecting hairs shed by my chocolate lab yesterday. In addition to fur, chickadees line their nest with grass (not available yet here), down and moss (hard to come by with two feet of snow still on the ground). Chickadees are able to nest this early in part because they nest in cavities, which offer them protection from the elements. Not having bills strong enough to hammer out cavities in living trees, chickadees rely heavily on rotting stumps for nest sites — the wood in them is punky and easy to remove. Birch, poplar and sugar maple snags and stumps are preferred nesting trees. If you want to provide chickadees and other birds with nesting material, take advantage of the fact that dogs and cats are shedding now, and recycle their fur.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Tufted Titmice Caching Seeds for Winter Consumption

Tufted Titmice and Black-capped Chickadees are in the same family (Paridae), and share several traits, one of which has to do with securing food. They are both frequent visitors of bird feeders where they not only take seeds and soon thereafter consume them, but they also collect and cache food throughout their territory for times when there is a scarcity of food. Tufted Titmice usually store their seeds within 130 feet of the feeder. They take only one seed per trip and usually shell the seeds before hiding them.

Tufted Titmice and Black-capped Chickadees are in the same family (Paridae), and share several traits, one of which has to do with securing food. They are both frequent visitors of bird feeders where they not only take seeds and soon thereafter consume them, but they also collect and cache food throughout their territory for times when there is a scarcity of food. Tufted Titmice usually store their seeds within 130 feet of the feeder. They take only one seed per trip and usually shell the seeds before hiding them.

In contrast to most species of titmice and chickadees, young Tufted Titmice often remain with their parents during the winter and then disperse later in their second year. Some yearling titmice even stay on their natal territory and help their parents to raise younger siblings.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Honeybee Scavenger

If the weather warms up sufficiently in January or February, honeybees take advantage of it and use this opportunity to leave their hive to rid themselves of waste that they have accumulated since their last flight and to remove the bodies of dead honeybees. They don’t fly very far before dropping either their waste or their dead comrades on the snow. This ritual is quickly noted and taken advantage of by animals that are not hive dwellers and need constant fuel in order to survive the cold. Black-capped chickadees are one of these animals – the chickadee in this photograph repeatedly landed on the hive body, and if a dead bee was available at the hive entrance, the chickadee helped itself to it. Otherwise it would survey the snow in front of the hive and then dart down to scoop up a bee in its beak before flying off to a branch to consume its nutritious meal. (Note dead bees at the hive opening, awaiting being taken on their final flight. Screening keeps mice out, but allows bee to enter and exit.) Thanks to Chiho Kaneko and Jeffrey Hamelman for photo op.

If the weather warms up sufficiently in January or February, honeybees take advantage of it and use this opportunity to leave their hive to rid themselves of waste that they have accumulated since their last flight and to remove the bodies of dead honeybees. They don’t fly very far before dropping either their waste or their dead comrades on the snow. This ritual is quickly noted and taken advantage of by animals that are not hive dwellers and need constant fuel in order to survive the cold. Black-capped chickadees are one of these animals – the chickadee in this photograph repeatedly landed on the hive body, and if a dead bee was available at the hive entrance, the chickadee helped itself to it. Otherwise it would survey the snow in front of the hive and then dart down to scoop up a bee in its beak before flying off to a branch to consume its nutritious meal. (Note dead bees at the hive opening, awaiting being taken on their final flight. Screening keeps mice out, but allows bee to enter and exit.) Thanks to Chiho Kaneko and Jeffrey Hamelman for photo op.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Bird Feeding – Does It Foster Dependency?

Decades ago birds remaining in the Northeast in the winter almost exclusively survived on weed seeds and insects they gleaned from crevices in tree bark. Today, nearly one-third of American adults provide about a billion pounds of bird seed each year, to say nothing of suet, seed cakes, etc. Should we be worried about creating a population of food-dependent wintering birds? Studies suggest that this is not the case. Researchers (this is going to sound cruel) removed feeders from woodlands where Black-capped Chickadees had been fed for the previous 25 years, and compared survival rates with those of chickadees in a nearby woodland where there had been no feeders. They documented that the chickadees familiar with feeders were able to switch back immediately to foraging for natural foods and survived the winter as well as chickadees that lived where no feeders had been placed. Not only did the feeder-fed birds not lose their ability to find food, but research also showed that food from feeders had made up only 21 percent of the birds’ daily energy requirement in the previous two years. This is not to say that there aren’t negative aspects to feeding birds, such as window collisions, disease, house cats, etc., but one thing luring birds to our houses for a closer look doesn’t do is destroy their innate ability to find food. (Photo is of a Red-breasted Nuthatch.)

Decades ago birds remaining in the Northeast in the winter almost exclusively survived on weed seeds and insects they gleaned from crevices in tree bark. Today, nearly one-third of American adults provide about a billion pounds of bird seed each year, to say nothing of suet, seed cakes, etc. Should we be worried about creating a population of food-dependent wintering birds? Studies suggest that this is not the case. Researchers (this is going to sound cruel) removed feeders from woodlands where Black-capped Chickadees had been fed for the previous 25 years, and compared survival rates with those of chickadees in a nearby woodland where there had been no feeders. They documented that the chickadees familiar with feeders were able to switch back immediately to foraging for natural foods and survived the winter as well as chickadees that lived where no feeders had been placed. Not only did the feeder-fed birds not lose their ability to find food, but research also showed that food from feeders had made up only 21 percent of the birds’ daily energy requirement in the previous two years. This is not to say that there aren’t negative aspects to feeding birds, such as window collisions, disease, house cats, etc., but one thing luring birds to our houses for a closer look doesn’t do is destroy their innate ability to find food. (Photo is of a Red-breasted Nuthatch.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Did you know…

Black-capped Chickadees actually refresh their brains once a year. According to Cornell’s Laboratory of Ornithology, every autumn Black-capped Chickadees allow brain neurons containing old information to die, replacing them with new neurons so they can adapt to changes in their social flocks and environment.

Black-capped Chickadees actually refresh their brains once a year. According to Cornell’s Laboratory of Ornithology, every autumn Black-capped Chickadees allow brain neurons containing old information to die, replacing them with new neurons so they can adapt to changes in their social flocks and environment.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

There are roughly 85 species of North American birds that are cavity nesters – birds that excavate nesting holes, use cavities resulting from decay (natural cavities), or use holes created by other species in dead or deteriorating trees. Many of them get a jump start on open-nesting birds, due to added protection from the elements. Barred owls, titmice, chickadees, wood ducks, woodpeckers, bluebirds, mergansers – many have chosen a nest site and are busy excavating, lining a cavity or laying eggs long before many other species have even returned to their breeding grounds.

There are roughly 85 species of North American birds that are cavity nesters – birds that excavate nesting holes, use cavities resulting from decay (natural cavities), or use holes created by other species in dead or deteriorating trees. Many of them get a jump start on open-nesting birds, due to added protection from the elements. Barred owls, titmice, chickadees, wood ducks, woodpeckers, bluebirds, mergansers – many have chosen a nest site and are busy excavating, lining a cavity or laying eggs long before many other species have even returned to their breeding grounds. The phenomenon of North American birds being killed by becoming entangled in Common Burdock (Arctium minus) has been documented since at least 1909, when one observer (in A.C. Bent’s compilation) described finding a multitude of Golden-crowned Kinglets in Common Burdock’s grasp:

The phenomenon of North American birds being killed by becoming entangled in Common Burdock (Arctium minus) has been documented since at least 1909, when one observer (in A.C. Bent’s compilation) described finding a multitude of Golden-crowned Kinglets in Common Burdock’s grasp: A number of insects cause goldenrod plants to form galls – abnormal growths that house and feed larval insects. The Goldenrod Ball Gall is caused by a fly, Eurosta solidaginis. The fly lays an egg on the stem of a Canada Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) plant in early spring, the egg hatches and the larva burrows its way into the stem; the plant reacts by forming a gall around the larva. The larva overwinters inside the gall, pupates in late winter and emerges in early spring as an adult fly. Prior to pupating, the larva chews an exit tunnel to, but not through, the outermost layer of gall tissue. (As an adult fly it will not have chewing mouthparts so it is necessary to do this work while in the larval stage.)

A number of insects cause goldenrod plants to form galls – abnormal growths that house and feed larval insects. The Goldenrod Ball Gall is caused by a fly, Eurosta solidaginis. The fly lays an egg on the stem of a Canada Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) plant in early spring, the egg hatches and the larva burrows its way into the stem; the plant reacts by forming a gall around the larva. The larva overwinters inside the gall, pupates in late winter and emerges in early spring as an adult fly. Prior to pupating, the larva chews an exit tunnel to, but not through, the outermost layer of gall tissue. (As an adult fly it will not have chewing mouthparts so it is necessary to do this work while in the larval stage.)

What Other Naturally Curious People Are Saying