Stabilimenta

Certain spiders, most of which are diurnal orb weavers, create zigzag silk designs on their webs called stabilimenta. A stabilimentum may be a single zigzag line, a combination of lines, or even a spiral whorl in the web’s center.

Theories abound as to the function of these adornments — originally they were thought to stabilize the web (because they are so loosely attached to the web this theory no longer holds water). It was also thought that because silk reflects UV light, it might be an enhanced way of attracting insects, but stabilimenta are not sticky, so that theory also is questionable.

Spiders that incorporate stabilimenta into their webs build their webs out in the open, during the day, and don’t rebuild their web every day. Nocturnal spiders and spiders that make webs in more secluded areas seem not to have stabilimenta. And diurnal spiders that remake their web every day don’t have them either. Much time and energy is expended spinning a web, and research shows that webs that have stabilimenta are, for the most part, avoided by birds. Thus, the prevailing theory is that stabilimenta are a kind of billboard that make birds aware of webs containing them. (Photo: Black-and Yellow Argiope web & stabilimenta)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Leaf-curling Sac Spiders Guarding Eggs

While all spiders spin silk, not all spiders make webs with their silk. Some spiders actively hunt prey instead of passively catching it in a web, including Leaf-curling Sac Spiders. They utilize their silk to form a protective brooding chamber for their eggs by stitching the underside of a leaf together. Within this shelter the mother spider first constructs an egg sac from strong silk that is tough enough to protect her developing offspring from the elements. She then deposits her eggs inside it, fertilizing them as they emerge. A single egg sac may contain just a few eggs, or several hundred, depending on the species. The mother spider remains within the shelter protecting her eggs until they hatch. Look for these spider shelters on the under side of grape leaves.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Spiders On Snow

The internal body temperature of spiders is variable and tends to fluctuate with their environment. This means that the cold temperatures of winter pose a challenge. Spiders meet this challenge in one of several ways. A majority (as many as 85%) of species crawl under the leaf litter, shut their metabolism way down and become dormant; some species mate, lay eggs and die; and some remain active.

It is not unusual to come across tiny active spiders on top of the snow, especially on sunny winter days. If it’s particularly cold, they may have their legs pulled in and appear lifeless. When their body is sufficiently warmed up, they will resume crawling across the snow.

The metabolism rate of spiders that remain active through the winter is elevated, making starvation as big a threat as freezing. They must find food (springtails and other invertebrates) in order to sustain themselves. Some of these spiders can remain active until their body temperature is 25 F degrees when they will go dormant like other spiders. They cannot survive If their internal temperature drops to 19 F. degrees. (Source, Vermont Center for Ecostudies) (Photo: active spider surviving despite loss of one leg)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

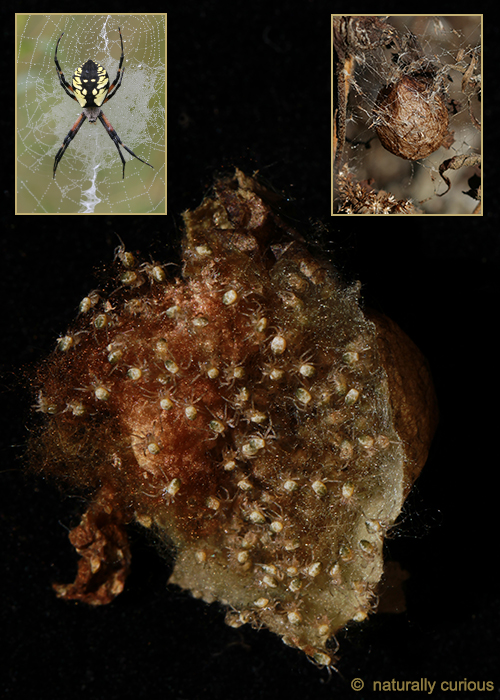

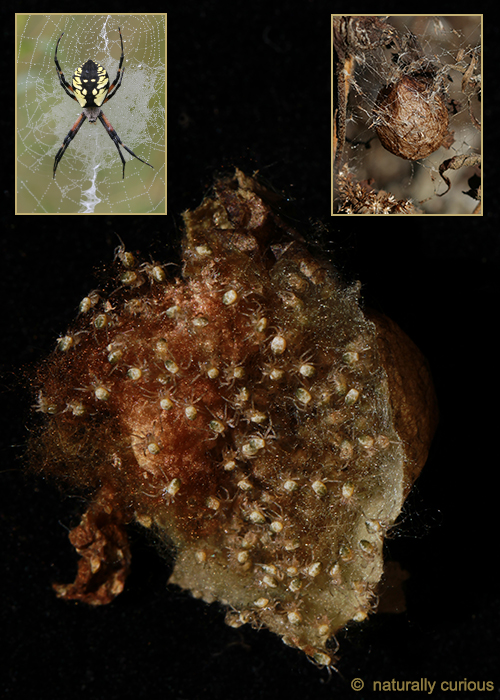

Black-and-Yellow Argiope Spiderlings Hatching

Some species of spiders (including wolf and jumping spiders) overwinter as young adults and mate/lay eggs in the spring. Many spiders, however, mate in the fall, after which they lay eggs and die. Their white or tan egg sacs are a familiar sight at this time of year. One might assume that these species overwinter as eggs inside their silken sacs, but this is rarely the case as spider eggs can’t survive being frozen. Spider eggs laid in the fall hatch shortly thereafter and the young spiders spend the winter inside their egg sac.

Although egg sacs provide a degree of shelter (the interior is packed with very fine, very soft silken threads), the newly-hatched spiderlings do have to undergo a process of “cold hardening” in the fall in order to survive the winter. On nights that go down into the 40’s and high 30’s, these young spiders start producing antifreeze compounds, which lower the temperature at which they freeze. By the time freezing temperatures occur, the spiders are equipped to survive the winter inside their egg sac – as spiderlings, not eggs. (Photos: Black-and-Yellow Argiope egg sac and spiderlings – egg sac had been pecked open by a bird)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Clover Mites

You may have come across a Clover Mite (Bryobia praetiosa) either on your lawn, in the woods or inside your house. While they are closely related to ticks, there is no cause for alarm as they do not bite and are not harmful to humans. These tiny, pin head-size mites feed on the sap of clover, grasses and roughly 200 other flowering plants.

All Clover Mites are female — they reproduce parthenogenetically and do not need males in order for their eggs to be viable. The (up to 70) eggs they lay and the larvae are bright red, while adults are reddish-brown. Clover Mites are extremely common this time of year, as well as in the fall.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Crab Spiders Active

Trailing Arbutus (Epigaea repens) is one of our earliest spring wildflowers. Sometime in April or May the creeping, leathery, evergreen leaves of this plant suddenly come alive with white or pink tubular flowers. While they are delightful to look at, their fragrance is what truly sets them apart from many other plants that flower this time of year.

Trailing Arbutus (Epigaea repens) is one of our earliest spring wildflowers. Sometime in April or May the creeping, leathery, evergreen leaves of this plant suddenly come alive with white or pink tubular flowers. While they are delightful to look at, their fragrance is what truly sets them apart from many other plants that flower this time of year.

Because there aren’t that many insects about this early, nor flowering plants, insect predators can have a challenging time finding prey. The pictured crab spider chose its perch wisely: bumble bees are the main pollinators of Trailing Arbutus, and queens are out scouting for food as they begin to establish their colonies.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Some Spiders Still Active

Spiders are ectotherms – warmed and cooled by their environment. In the fall, those outdoor species that remain alive through the winter begin preparing themselves by producing antifreeze proteins that allow their tissues to experience below-freezing temperatures. When a small particle of ice first starts to form, the antifreeze proteins bind to it and prevent the water around it from freezing, thus preventing the growth of an ice crystal. Some species survive in temperatures as low as -5 degrees Celsius.

Spiders are ectotherms – warmed and cooled by their environment. In the fall, those outdoor species that remain alive through the winter begin preparing themselves by producing antifreeze proteins that allow their tissues to experience below-freezing temperatures. When a small particle of ice first starts to form, the antifreeze proteins bind to it and prevent the water around it from freezing, thus preventing the growth of an ice crystal. Some species survive in temperatures as low as -5 degrees Celsius.

The pictured hammock spider, still active in late October, is nourishing itself by drinking the dissolved innards of a fall-flying March fly, whose name comes from the predominantly springtime flight period of most March Flies (of the 32 species in the genus Bibio in North America, only three fly in fall).

A common belief is that once cold weather appears, outdoor spiders seek shelter inside houses. In fact, only about 5% of the spiders you find in your house lived outside before coming into your house, according to Seattle’s Burk Museum. The reason people tend to notice them more inside may be because sexually mature male spiders become more active in the fall, wandering far and wide in search of mates.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to https://naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

How Webs Work

Spiders produce different types of silk for different purposes, including draglines, egg sacs, ballooning, building a web and wrapping prey. Much of the silk spiders use to spin webs has a sticky consistency, in order to catch flying insects. It turns out that sticky silk isn’t the only reason spider webs are such efficient insect catchers.

Spiders produce different types of silk for different purposes, including draglines, egg sacs, ballooning, building a web and wrapping prey. Much of the silk spiders use to spin webs has a sticky consistency, in order to catch flying insects. It turns out that sticky silk isn’t the only reason spider webs are such efficient insect catchers.

According to scientists at Oxford University, not only is much of a spider’s web silk sticky, but it is coated with a glue that is electrically conductive. This glue causes spider webs to reach out and grab all charged particles that fly into it, from pollen to grasshoppers. Physics accounts for the web moving toward all airborne objects, whether they are positively or negatively charged.

According to Prof. Vollrath of Oxford University, electrical attraction also drags airborne pollutants (aerosols, pesticides, etc.) to the web. For this reason, it’s been suggested that webs could be a valuable resource for environmental monitoring. (Thanks to Elizabeth Walker and Linda Fuerst for introducing me to this phenomenon.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to https://naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Young Wolf Spiders Dispersing

Earlier in the summer, you may have glimpsed a spider carrying its white egg sac around with it, clasping it with the spinnerets at the end of its abdomen. When the spiderlings hatch they crawl up their mother’s legs onto her abdomen, latch onto special knob-shaped hairs, and ride around with her for several weeks (see inset). Only wolf spiders carry their egg sacs and offspring in this manner.

Earlier in the summer, you may have glimpsed a spider carrying its white egg sac around with it, clasping it with the spinnerets at the end of its abdomen. When the spiderlings hatch they crawl up their mother’s legs onto her abdomen, latch onto special knob-shaped hairs, and ride around with her for several weeks (see inset). Only wolf spiders carry their egg sacs and offspring in this manner.

After molting, which occurs mid-summer, the young spiders disperse. Eventually the mother is free to hunt for prey without the encumbrance of hitch-hiking offspring. If you look closely at the pictured wolf spider, you may be able to make out the last lingering spiderling located at the junction of the wolf spider’s cephalothorax and abdomen.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to https://naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Spiders Crawling On The Snow

Most adult spiders (as many as 85% of temperate zone species) are dormant during the winter, seeking shelter beneath the leaf litter. Their metabolism slows and their need for food is greatly reduced. Other species die at the end of the summer, and their eggs overwinter, protected inside silken sacs. A third, even smaller, group of spiders remains active through the winter.

Most adult spiders (as many as 85% of temperate zone species) are dormant during the winter, seeking shelter beneath the leaf litter. Their metabolism slows and their need for food is greatly reduced. Other species die at the end of the summer, and their eggs overwinter, protected inside silken sacs. A third, even smaller, group of spiders remains active through the winter.

Spiders’ body temperatures vary significantly, heavily influenced by their environment. Many spiders that remain active year round seek shelter in the subnivean layer between the ground and snow, where the temperature (+/-32°F.) is often warmer than the air. Occasionally, however, they do appear on the surface of the snow, where they are exposed to the wintery blasts of cold air.

Scientists don’t know exactly how these active spiders survive the cold. Some species can tolerate temperatures as low as -4° F.°. Glycerol acts as a type of anti-freeze for these arachnids, but its effect is marginal. In order to survive, some species bask in the sun and derive energy from their diet of snow fleas (a type of springtail) and other small prey, but these strategies don’t totally explain their ability to survive a New England winter. Species of spiders in the families Linyphiidae and Tetragnathidae (see photo) are often what you see crawling on top of the snow.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to https://naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Spider Web-filled Fields

While perhaps not as impressive as the square miles of fields and trees that have been totally covered in spider webs in New Zealand, Pakistan, Tasmania and Southern Australia over the past year or two, New England does have its share of fields adorned with spider silk. The silk in foreign lands was the result of spiders ballooning (floating aloft on gossamer they spin that is lifted by the wind) in spring – an effective means of dispersal. The silk we see highlighted in fields in the early morning dew of autumn in New England serves as webs, or traps, for unsuspecting insects. A majority of these webs are made by grass spiders, many of which weave a horizontal sheet of silk that have a funnel often on one side leading down to a spider hide-a-way. When vibrations alert the spider to a potential meal that is caught in its web, it rushes out, injects the insect with digestive enzymes, and drags it back into its retreat where it begins to feed.

While perhaps not as impressive as the square miles of fields and trees that have been totally covered in spider webs in New Zealand, Pakistan, Tasmania and Southern Australia over the past year or two, New England does have its share of fields adorned with spider silk. The silk in foreign lands was the result of spiders ballooning (floating aloft on gossamer they spin that is lifted by the wind) in spring – an effective means of dispersal. The silk we see highlighted in fields in the early morning dew of autumn in New England serves as webs, or traps, for unsuspecting insects. A majority of these webs are made by grass spiders, many of which weave a horizontal sheet of silk that have a funnel often on one side leading down to a spider hide-a-way. When vibrations alert the spider to a potential meal that is caught in its web, it rushes out, injects the insect with digestive enzymes, and drags it back into its retreat where it begins to feed.

What’s Inside A Spider Egg Sac This Time of Year May Surprise You

Some species of spiders (including wolf and jumping spiders) overwinter as young adults and mate/lay eggs in the spring. Many spiders, however, mate in the fall, after which they lay eggs and die. Their white or tan egg sacs are a familiar sight at this time of year. One might assume that these species overwinter as eggs inside their silken sacs, but this is rarely the case as spider eggs can’t survive being frozen. Spider eggs laid in the fall hatch shortly thereafter and the young spiders spend the winter inside their egg sac.

Although egg sacs provide a degree of shelter (the interior is packed with very fine, very soft silken threads), the newly-hatched spiderlings do have to undergo a process of “cold hardening” in the fall in order to survive the winter. On nights that go down into the 40’s and high 30’s, these young spiders start producing antifreeze compounds, which lower the temperature at which they freeze. By the time freezing temperatures occur, the spiders are equipped to survive the winter inside their egg sac – as spiderlings, not eggs. (Photos: Black-and-Yellow Argiope, Black-and-Yellow Argiope egg sac, Black-and-Yellow Argiope spiderlings inside egg sac)

What’s Inside A Spider’s Egg Sac This Time Of Year May Surprise You!

Some species of Northeastern spiders (including wolf and jumping spiders) overwinter as young adults and mate/lay eggs in the spring. Many spiders, however, mate in the fall, after which they lay eggs and die. Their white or tan egg sacs are a familiar sight at this time of year. One might assume that these species overwinter as eggs inside their silken sacs but this is rarely the case, as spider eggs can’t survive being frozen. Spider eggs laid in the fall hatch shortly thereafter and spend the winter as young spiders inside their egg sac.

Although egg sacs provide a degree of shelter, the newly-hatched spiderlings do have to undergo a process of “cold hardening” in the fall in order to survive the winter. On nights that go down into the 40’s and high 30’s, these young spiders start producing antifreeze compounds, which lower the temperature at which they freeze. By the time freezing temperatures occur, the spiders are equipped to deal with them throughout the winter – as spiderlings, not eggs. (Photo: Black-and-Yellow Argiope (Argiope aurantia) egg sac)

Harvestmen Harvesting

Like their relatives – spiders, mites, ticks and scorpions – Daddy Longlegs, or Harvestmen, have eight legs (the second, longer, pair of legs are used as antennae). Of all the arachnids, spiders resemble Harvestmen most closely. However, there are distinct differences between the two orders. Unlike spiders, the two main body sections of Harvestmen are nearly joined and appear as one structure. Harvestmen have no spinnerets nor do they possess poison glands. They also do not have the enzymes spiders have that are capable of breaking down the insides of their prey into liquid. Harvestmen ingest small particles, breaking them down with their chelicerae, or mouthparts, which resemble miniature, toothed lobster claws. One would surmise from this photograph that the legs of flies must lack the nutrition worthy of mastication.

Like their relatives – spiders, mites, ticks and scorpions – Daddy Longlegs, or Harvestmen, have eight legs (the second, longer, pair of legs are used as antennae). Of all the arachnids, spiders resemble Harvestmen most closely. However, there are distinct differences between the two orders. Unlike spiders, the two main body sections of Harvestmen are nearly joined and appear as one structure. Harvestmen have no spinnerets nor do they possess poison glands. They also do not have the enzymes spiders have that are capable of breaking down the insides of their prey into liquid. Harvestmen ingest small particles, breaking them down with their chelicerae, or mouthparts, which resemble miniature, toothed lobster claws. One would surmise from this photograph that the legs of flies must lack the nutrition worthy of mastication.

Wolf Spiders: Maternal Duties Coming To An End

Just a few days ago, this adult female wolf spider’s abdomen was covered three-spiders-deep with newborn wolf spiderlings. Wolf spiders, unlike most spiders, do not abandon their eggs. They carry their egg sac around with them until the eggs hatch, grasping it with spinnerets located at the tip of their abdomen. Not only does the female not desert her eggs, but she also provides protection for her newborn spiders. After hatching, the several dozen or more young crawl up onto her abdomen, where they ride around for several days. Eventually they drop off and begin a life of their own. In this photo, only three spiderlings remain (look closely) and they abandoned ship within the hour.

Just a few days ago, this adult female wolf spider’s abdomen was covered three-spiders-deep with newborn wolf spiderlings. Wolf spiders, unlike most spiders, do not abandon their eggs. They carry their egg sac around with them until the eggs hatch, grasping it with spinnerets located at the tip of their abdomen. Not only does the female not desert her eggs, but she also provides protection for her newborn spiders. After hatching, the several dozen or more young crawl up onto her abdomen, where they ride around for several days. Eventually they drop off and begin a life of their own. In this photo, only three spiderlings remain (look closely) and they abandoned ship within the hour.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Arachnid Anomaly

Wolf spiders and nursery web spiders look a lot alike. One way to tell one from the other is to look at the arrangement of the spider’s eyes. Nursery web spiders (family Pisauridae) have two rows of four eyes each, all roughly the same size. Wolf spiders (family Lycosidae) have a row of four small eyes, above which there are two large eyes, with two very small eyes a short distance behind them. From looking at the eyes of the pictured spider, one would assume it was a wolf spider (smallest, topmost eyes are not visible).

However, a second way to distinguish these two families of spiders is to notice how the females carry their egg sacs (the females of both species carry their egg sacs with them wherever they go). Wolf spiders attach their egg sacs to the spinnerets located at the tip of their abdomen, whereas nursery web spiders carry them in their pedipalps (two appendages that look like, but aren’t, legs ) and mouthparts, as seen in this photo.

Thus, this particular spider has wolf spider eye arrangement, and practices a nursery web spider egg sac-carrying technique. My assumption is that this is a mixed up wolf spider or one with tired spinnerets.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button

Crab Spiders Well Camouflaged

Some say crab spiders derived their common name from the way in which they move sideways like a crab. Others liken their first two (longer) pairs of legs to those of crabs. Still others feel their short, wide, flat bodies resemble those of crabs. Whatever the source of their name, this group of spiders consists of ambush predators. Instead of stalking their prey, or catching them in a silk web, crab spiders tend to stay put (often on flowers), and blend into the background as much as possible in order to pounce on unsuspecting prey.

Some say crab spiders derived their common name from the way in which they move sideways like a crab. Others liken their first two (longer) pairs of legs to those of crabs. Still others feel their short, wide, flat bodies resemble those of crabs. Whatever the source of their name, this group of spiders consists of ambush predators. Instead of stalking their prey, or catching them in a silk web, crab spiders tend to stay put (often on flowers), and blend into the background as much as possible in order to pounce on unsuspecting prey.

In order to meet with success, crab spiders camouflage themselves extremely well. Some resemble bird droppings, while others look like fruits, leaves, grass, or flowers. The Goldenrod Crab Spider, a fairly common white or yellow crab spider with pink markings, is capable of changing its color from white to yellow over a period of days, depending on the color of the flower it is on. (Crab spiders often remain in the same location for days and even weeks.) The likeness of the pictured crab spider to one of the Turtlehead’s buds is surely not coincidental.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go tohttp://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Wolf Spiders Closely Guarding Egg Sacs

Spinnerets, located at the far end of a spider’s abdomen, serve as spigots through which silk is exuded, but they also have another function for some species of arachnids. Female wolf spiders use their spinnerets to grasp their eggs sacs, enabling them to carry and guard their eggs until they hatch. In order not to damage the eggs when she moves, the spider tilts her abdomen up slightly. Catching prey with this added encumbrance and in this position must take great skill. Once the wolf spider’s eggs hatch, the young climb up on top of the abdomen where they spend their first days before dispersing. (Nursery web spiders also carry their egg sacs with them, but clasp them with their jaws, or chelicerae, and small, leg-like appendages called pedipalps.)

Spinnerets, located at the far end of a spider’s abdomen, serve as spigots through which silk is exuded, but they also have another function for some species of arachnids. Female wolf spiders use their spinnerets to grasp their eggs sacs, enabling them to carry and guard their eggs until they hatch. In order not to damage the eggs when she moves, the spider tilts her abdomen up slightly. Catching prey with this added encumbrance and in this position must take great skill. Once the wolf spider’s eggs hatch, the young climb up on top of the abdomen where they spend their first days before dispersing. (Nursery web spiders also carry their egg sacs with them, but clasp them with their jaws, or chelicerae, and small, leg-like appendages called pedipalps.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Sheet Web Weavers Still Active

Spider webs are constructed in a variety of shapes, for which many of them are named. Among others are orb webs, triangle webs, mesh webs and sheet webs. One of the most prevalent types of spider webs seen this late in the year is the sheet web, made by members of the Lynyphiidae family.

Spider webs are constructed in a variety of shapes, for which many of them are named. Among others are orb webs, triangle webs, mesh webs and sheet webs. One of the most prevalent types of spider webs seen this late in the year is the sheet web, made by members of the Lynyphiidae family.

Several different web designs are found in this family including the bowl and doily, dome, and sheet. Tiny sheet web weavers spin small horizontal sheets of webbing and then hang upside-down underneath their web. Some species make two layers and hide between them for protection. When a small insect walks across the web, the spider bites through the silk, grabs its prey, pulls it through the web and eats (actually drinks) it.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Spiderlings Dispersing

Although many spider eggs hatch in the spring, there are some that hatch in the fall. Most spiderlings stay within the egg sac until they undergo their first molt – their small cast skins can be seen inside the old egg sac. After molting they emerge and cluster together, still living largely upon the remnants of yolk sac in their abdomens. In several days the spiderlings are ready to disperse, which is necessary to avoid competition for food and prevent cannibalism among the hungry siblings.

Although many spider eggs hatch in the spring, there are some that hatch in the fall. Most spiderlings stay within the egg sac until they undergo their first molt – their small cast skins can be seen inside the old egg sac. After molting they emerge and cluster together, still living largely upon the remnants of yolk sac in their abdomens. In several days the spiderlings are ready to disperse, which is necessary to avoid competition for food and prevent cannibalism among the hungry siblings.

Some species, especially ground dwellers, disperse by walking, often over relatively short distances. Others, particularly foliage dwellers and many web builders, mainly disperse by ballooning. To balloon, spiderlings crawl to the top of a blade of grass, a twig or a branch, point their abdomens up in the air and release a strand of silk. Air currents catch the silk, often called gossamer, and lift the spider up and carry it off. Aerial dispersal may take a spiderling just a few feet away or much, much farther – spiderlings have been found as far as 990 miles from land. (Charles Darwin noted spiderlings landing on the rigging of the Beagle, 62 miles out to sea).

Spiders Molting Exoskeletons

Like other arthropods, spiders have a protective hard exoskeleton that is flexible enough for movement, but can’t expand like human skin. Thus, they have to shed, or molt, this exoskeleton periodically throughout their lives as they grow, and replace it with a new, larger exoskeleton. Molting occurs frequently when a spider is young, and some spiders may continue to molt throughout their life.

Like other arthropods, spiders have a protective hard exoskeleton that is flexible enough for movement, but can’t expand like human skin. Thus, they have to shed, or molt, this exoskeleton periodically throughout their lives as they grow, and replace it with a new, larger exoskeleton. Molting occurs frequently when a spider is young, and some spiders may continue to molt throughout their life.

At the appropriate time, hormones tell the spider’s body to absorb some of the lower cuticle layer in the exoskeleton and begin secreting cuticle material to form the new exoskeleton. During the time that leads up to the molt (pre-molt period), a new, slightly larger, inner exoskeleton develops and is folded up under the existing exoskeleton. This new soft exoskeleton is separated from the existing one by a thin layer called the endocuticle. During the pre-molt period the spider secretes fluid that contains digestive enzymes between the new inner and old outer exoskeletons. This fluid digests the endocuticle that separates the two exoskeletons, making it easier for them to separate.

Once the endocuticle is completely digested the spider is ready to complete the molt. At this point a spider pumps hemolymph (spider blood) from its abdomen into its cephalothorax in order to split its carapace, or headpiece, open. The spider then slowly pulls itself out of the old exoskeleton through this opening.

Typically, the spider does most of its growing immediately after losing the old exoskeleton, while the new exoskeleton is highly flexible. The new exoskeleton is very soft, and until it hardens, the spider is particularly vulnerable to attack.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Sac Spider Shelter Serves as Nursery & Coffin

It is not unusual to come across a rolled-up leaf – the larvae of many moths create shelters in this fashion, using silk as their thread. Less common, and more intricate, are the leaf “tents” of sac spiders. With great attention paid to the most minute details, a female sac spider bends a leaf (often a monocot, with parallel veins, as in photo) in two places and seals the edges (that come together perfectly) with silk. She then spins a silk lining for this tent, inside of which she lays her eggs. There she spends the rest of her life, guarding the eggs. She will die before the eggs hatch and her body will serve as her offspring’s first meal. (Thanks to Ginny Barlow for photo op.)

It is not unusual to come across a rolled-up leaf – the larvae of many moths create shelters in this fashion, using silk as their thread. Less common, and more intricate, are the leaf “tents” of sac spiders. With great attention paid to the most minute details, a female sac spider bends a leaf (often a monocot, with parallel veins, as in photo) in two places and seals the edges (that come together perfectly) with silk. She then spins a silk lining for this tent, inside of which she lays her eggs. There she spends the rest of her life, guarding the eggs. She will die before the eggs hatch and her body will serve as her offspring’s first meal. (Thanks to Ginny Barlow for photo op.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Predator Eating Predator

The Six-spotted Fishing Spider, Dolomedes triton, is an arachnid in the nursery web spider family Pisauridae. As its name implies, the Six-spotted Fishing Spider does occasionally eat small fish, but also consumes other invertebrates and tadpoles. The hunting techniques of fishing spiders are varied. Often they sit patiently during the day, waiting hours with their legs stretched out for an unsuspecting insect (such as the pictured Dot-tailed Whiteface dragonfly) to land on the same lily pad or leaf that the spider is sitting on. They can and do walk on water as well as dive up to seven inches deep in order to catch aquatic prey. The Six-spotted Fishing Spider in this photograph has removed the head of its prey and is drinking its liquefied innards.

The Six-spotted Fishing Spider, Dolomedes triton, is an arachnid in the nursery web spider family Pisauridae. As its name implies, the Six-spotted Fishing Spider does occasionally eat small fish, but also consumes other invertebrates and tadpoles. The hunting techniques of fishing spiders are varied. Often they sit patiently during the day, waiting hours with their legs stretched out for an unsuspecting insect (such as the pictured Dot-tailed Whiteface dragonfly) to land on the same lily pad or leaf that the spider is sitting on. They can and do walk on water as well as dive up to seven inches deep in order to catch aquatic prey. The Six-spotted Fishing Spider in this photograph has removed the head of its prey and is drinking its liquefied innards.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

What Other Naturally Curious People Are Saying