Cedar-Apple Rust Galls

Galls are abnormal plant growths caused by various agents including insects, mites, nematodes, fungi, bacteria and viruses. During the summer spores of a particular fungus cause the formation of brown Cedar-Apple Rust galls (Gymnosporangium juniperivirginianae) on Eastern Red Cedar trees. Members of the fungal family Pucciniaceae are known as rusts because the color of many is orange or reddish at some point in their life cycle.

This fungus requires two hosts, Eastern Red Cedar and primarily apples or crabapples, to complete its life cycle. The two host trees are usually located within a mile of each other. When the Cedar-Apple Rust galls on cedar trees get wet from spring rains, orange, spore-filled fingers or horns, called telia, emerge from pores in the gall. As the horns absorb water, they become jelly-like and swollen (see inset). When the jelly dries, the spores are carried by the wind to apple trees, where they cause a brownish mottling on apples, referred to as Cedar-Apple Rust, which makes apples difficult for growers to sell, even though it doesn’t affect the flavor or texture of infected apples. The rust produces spores on the underside of apple leaves in late summer, which, if they land on Eastern Red Cedar trees, cause galls to form, thereby continuing the cycle.

Spores produced on apple trees do not infect apple trees, only cedar; spores produced on cedar trees infect only apple trees. (Photo: Brown winter form of Cedar-Apple Rust gall & (inset) orange spring form of Cedar-Apple Rust gall. Blue “fruit” on Eastern Red Cedar branch is actually a cedar cone.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Shaggy Manes Dissolving

Shaggy Mane, Coprinus comatus, is one of a group of mushrooms known as Inky Caps. Both of these common names reflect the appearance of the mushroom at different stages of its development – the cap has white, shaggy scales, and as the mushroom matures its gills liquefy into a black substance that was once used as ink.

Most Inky Caps have gills that are very thin and very close to one another, which does not allow for easy release of the spores. In addition, the elongated shape of this mushroom does not allow for the spores to get caught in air currents as in most other mushrooms. The liquefication/self-digestion process is actually a strategy to disperse spores more efficiently. The gills liquefy from the bottom up as the spores mature. Thus the cap peels up and away, and the maturing spores are always kept in the best position for catching wind currents. This continues until the entire fruiting body has turned into black ink.

NB: WordPress has not been attaching the photograph that accompanies each post that is emailed to readers. I am working on getting it fixed, but meanwhile, if this continues, you can click on the title in the emailed version and it will take you to the Naturally Curious website, where you can see the photo. So sorry for the inconvenience.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Millipedes Migrating

We don’t often see millipedes because of their preference for secluded, moist sites where they feed on decaying vegetation and other organic matter. They are also more active at night, when the humidity is high. At this time of year, however, your chances of seeing a millipede are increased due to the fact that these invertebrates are migrating in search of overwintering sites. Adults overwinter in nooks and crannies that provide them with some protection. Many, like the one pictured, end up under loose bark.

Millipedes are harmless, so if you see one that accidentally found its way into your home, you can safely return it to the outdoors.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Snakes Basking & Brumating

Being ectothermic (unable to regulate their own body temperature) snakes cannot afford to spend the winter in a spot that freezes. After basking and feeding heavily in the late fall, they seek out sheltered caves, hollow logs, and burrows where they enter a state called brumation. Brumation is to reptiles what hibernation is to mammals – an extreme slowing down of one’s metabolism.

While similar, these two states have their differences. Hibernating mammals slow their respiration down, but they still require a fair amount of oxygen present to survive. Snakes can handle far lower oxygen demands and fluctuations than mammals. Also, hibernating mammals sleep the entire time during their dormancy, whereas snakes have periods of activity during brumation. If the weather is mild, they will take advantage of the opportunity to venture out and bask. They also need to drink during this period in order to avoid dehydration. (Photo: DeKay’s Brownsnake (Storeria dekayi) basking)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

White-crowned Sparrows Migrating

White-crowned Sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys) breed north of New England and overwinter south of New England. The only time we get to admire their elegant plumage is during migration, primarily in May and October.

White-crowned Sparrows are strong migrators (A migrating White-crowned Sparrow was once tracked moving 300 miles in a single night.) but they do have to stop and refuel along the way. Because they are now passing through New England, you may see what at first might appear to be a White-throated Sparrow, but is a White-crowned Sparrow. Their bold black-and-white striped crowns are one quick way to tell one species from another. (Immature birds have brown and gray stripes.) Look for them foraging in weeds along the roadside or in overgrown fields. About 93% of their diet is plant material, 74% of which is weed seeds.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

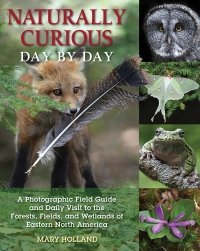

Reminder: 2021 Naturally Curious Calendar Orders Due By October 31st

Orders for the 2021 Naturally Curious Calendar can be placed now by writing to me at 505 Wake Robin Drive, Shelburne, VT 05482. The calendars are printed on heavy card stock and measure 11” x 17” when hanging. There is one full-page photograph per month. The calendars are $35.00 each (includes postage). Please specify the number of calendars you would like to order, the mailing address to which they should be sent and your email address (so I can easily and quickly contact you if I have any questions). Your check can be made out to Mary Holland.

Guaranteed orders can be placed up until October 31st. Orders placed after this date will be filled as long as my supply of extra calendars lasts. (To be candid, I have had so many last-minute requests (after the deadline) in past years that I have not been able to fill all of the orders, so if you want to be sure of having your order filled, I encourage you to place your order before October 31st . I hate to disappoint anyone.) Calendars will arrive at your door in early December in time for the New Year. Thank you so much!

White-tailed Deer Molting

The signs of fall are plentiful – skeins of migrating geese, disappearing insects, falling leaves. Another transformation that takes place in the fall (as well as spring) with White-tailed Deer and other mammals is the molting of a summer coat and the growing in of a winter coat.

The thinner summer coat of a White-tailed Deer consists of shorter, reddish hair. The shorter length of the hair allows the deer’s body heat to easily escape and the light color reflects rather than retains warmth from the sun. Come fall, deer molt the rusty red hairs of summer, and replace them with a coat consisting of longer, darker hairs. This grayish-brown hair is warmer and absorbs more of the sun’s warmth. A spring molt occurs in reverse.

The process of molting happens relatively fast and is often completed within two to three weeks. During this period, deer can look a bit ragged (see photo), as both the red summer hairs as well as the brown winter hairs are evident. If you see a deer at this time, it’s easy to assume that such a deer has mange, but it is just the way a seasonal molt takes place. (Photo by Erin Donahue)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Yellow-bellied Sapsucker & European Hornet Sign

Congratulations to “mariagianferrari,” who came the closest to solving the Mystery Photo when she correctly guessed that the missing bark was the result of a partnership between an insect and a Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varius). The sapsucker arrived first and pecked the vertical rows of rectangular holes in the trunk of the tree in order to obtain sap as well as the insects that the sap attracts. (Usually these holes are not harmful, but a tree may die if the holes are extensive enough to girdle the trunk or stem.)

The second visitor whose sign is apparent between the sapsucker holes is the European, or Giant, Hornet (Vespa crabro). This large (3/4″ – 1 ½ “) member of the vespid family was introduced to the U.S. about 200 years ago. Overwintering queens begin new colonies in the spring and the 200-400 workers of a colony then forage for insects including crickets, grasshoppers, large flies and caterpillars to feed to the larvae.

In addition, the workers collect cellulose from tree bark and decaying wood to expand their paper nest, which is what has occurred between the sapsucker holes, effectively girdling the apple tree. The nutritious sap that this collecting exposes is also consumed by the hornets. We don’t often witness this activity because most of it occurs at night.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Mystery Photo

Do you know who has visited this apple tree and left this sign? Hint: This is the work of two creatures whose identity will be disclosed in Friday’s post.

If you think you know who’s been here, go to the Naturally Curious blog and submit your answer under “Comments.” (Thanks to Jim Chadwick for the photograph, and Jan Gendreau for submitting it.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Canada Goose Migratory Formation

“V’s” of migrating Canada Geese are a common sight and sound in the Northeast during October. The inevitable question arises: why fly in a V formation? In part, because it conserves energy. But exactly how does it do this?

As the lead goose flaps, it creates tiny vortexes (circular patterns of rotating air) swirling off its wings as well as into the space behind it. The vortex behind a goose goes downward, while the vortexes on either side of its wings go up. If a goose flies directly behind the goose in front of it, air will be pushing it down. If it flies off to the outer side of the goose in front of it, air is pushing upward and the goose will get a slight lift, making flying easier.

Picture two geese flying behind and to the outer sides of the lead goose. Additional geese, in order to avoid the vortex behind the lead goose as well as the vortexes directly behind the next two geese, will fly behind and to the outside of the wings of the two birds in front of them, getting a lift and forming a “V.”

Because the lead goose has no vortex to get a lift from, it tires more easily than the other geese. It periodically falls back and is replaced by another goose in the formation. This cooperative process of taking turns leading the flock minimizes the need for the birds to stop and rest.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Bur Oak: An Uncommon Source of Acorns in the East

Oaks are generally divided into two major groups: red oaks and white oaks. Red oaks have bristle-tipped leaves, acorns with hairy shell linings and bitter seeds that mature in two seasons. White oaks have leaves lacking bristles on the lobes, acorns with a smooth inner surface that are sweet or slightly bitter and mature in one season.

Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa). also called Mossycup Oak, is in the white oak group and is easily identified by the corky ridges on its young branches, deeply furrowed bark and acorns with knobby-scaled caps (cupules) with a fringed edge. This member of the beech family (Fagaceae) derived its common name from the resemblance of its heavily fringed caps to the burs on a Chestnut tree, though the caps only half cover the nut. Common in central U.S., Bur Oak is relatively uncommon in New England, occurring in in central Maine, New Hampshire, the western edges of Massachusetts and Connecticut, and the Champlain Valley in Vermont.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

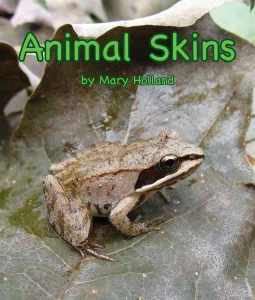

Northern Leopard Frogs Migrating

Northern Leopard Frogs (Lithobates pipiens) are often found in wet, grassy meadows where they spend the summer after breeding in a body of water. Come fall, they typically migrate towards the shoreline of a pond, traveling up to two miles in order to do so.

Northern Leopard Frogs cannot tolerate freezing temperatures, so as it begins cooling off in October and November, these irregularly-spotted amphibians seek protection by entering the water and spending the winter months hibernating on the bottom of the pond. They are sometimes covered with a thin layer of silt, sometimes not. Usually they clear the area either side of themselves in order to facilitate respiration. Movement, if there is any, is very slow.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Pollen Baskets

Due to their tolerance of cold temperatures, bumblebees can still be found foraging on late-blooming flowers such as New England Asters (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae). Most worker bees collect and carry pollen in a dense mass of elongated and often branched hairs (setae) on their hind legs called a scopa. Honeybees and bumblebees, however, have pollen baskets, or corbiculae, in which they place and carry pollen back to their hive. Pollen baskets consist of a polished cavity located on the tibia of each of their hind legs which is surrounded by a fringe of hairs. Pollen is pressed on to the pollen basket when it has been collected by the combs and brushes on the inside of the bee’s legs. The bumblebee moistens the pollen with some nectar to make it sticky and stay in the basket. The pollen is loaded at the bottom of the pollen basket, so the pollen that has been pushed towards the top is from flowers the bumblebee visited earliest on her foraging trip. When a pollen basket is full it can weigh as much as 0.01 gram and contain as much as 1,000,000 pollen grains.

Only queen bumblebees overwinter, and they must start a new colony in the spring. When the queen first emerges you can tell whether or not she has started a nest by looking at her pollen baskets. If she is carrying pollen then she has found a nest site.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Raccoon Latrines

A reliable way to determine an animal’s diet is to examine their scat, ideally several scats over the span of a few days, in every season. This is easily done with Raccoons, as they often create communal sites called latrines where they repeatedly defecate. The pictured latrine consists of several scats containing corn, apples and grapes.

Latrines are usually found at the base of trees, in forks of trees, or on raised areas such as fallen logs, stumps, or large rocks. Should you discover a latrine and your curiosity has you inspecting the scat contents, do so with caution. Raccoons are the primary host of Baylisascaris procyonis, a roundworm that is the cause of a fatal nervous system disease in wild animals. The eggs of Baylisascaris procyonis can be harmful to people if they are swallowed or inhaled. Raccoon roundworm eggs (invisible to the naked eye) are passed in the feces of infected raccoons at the rate of 20,000 eggs per gram of feces. Although human infections are rare, they can lead to irreversible brain, heart, and sometimes eye, damage and death.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

What Other Naturally Curious People Are Saying