Congratulations to Sharon Weizenbaum, Beth Herr and David Ascher for correctly identifying the Mystery Photo as the tip of the abdomen of a Common Walkingstick (Diapheromera femorata), also known as Devil’s Darning Needle, Devil’s/Witch’s Riding Horse, and Prairie Alligator due to its unusual shape. While the Common Walkingstick is a mere 3” long, the largest North American species can grow to 7” and one tropical species may reach 14”.

Congratulations to Sharon Weizenbaum, Beth Herr and David Ascher for correctly identifying the Mystery Photo as the tip of the abdomen of a Common Walkingstick (Diapheromera femorata), also known as Devil’s Darning Needle, Devil’s/Witch’s Riding Horse, and Prairie Alligator due to its unusual shape. While the Common Walkingstick is a mere 3” long, the largest North American species can grow to 7” and one tropical species may reach 14”.

The Walkingstick lives up to its name – it is easily mistaken for a twig with its slender body and legs. By remaining motionless during the day (or gently swaying in the wind like a leaf or twig would), and feeding on the leaves of various deciduous trees at night it avoids many predators with its physical and behavioral adaptations. The practice of using both camouflage and mimicry is referred to as crypsis.

Both the male and female Walkingstick possess a pair of appendages at the tip of their abdomen known as cerci. The cerci on a female are short and straight, while those on the male are longer and curved. They are sensory organs, but in addition, the male uses his cerci to grasp the female when mating with her (see inset). According to entomologist Dr. Gilbert Waldbauer, the cerci are very effective, allowing the male Walkingstick to clasp the female for many hours (weeks for some species) in order to prevent another male from mating with the female.

This is the time of year you are most likely to notice Walkingsticks, as this is when they are maturing and reproducing. Females drop their eggs to the ground from the canopy and because a portion of the outside (capitulum) of each egg is edible (like the elaiosomes of many spring ephemerals), ants carry the eggs below-ground to their nests and eat the capitulum, leaving the intact eggs to hatch and develop.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

August 24, 2020 | Categories: August, camouflage, Elaiosomes, Ephemerals, Insects, Mimicry, Uncategorized | Tags: Diapheromera femorata | 4 Comments

The survival of Viceroy butterflies in all of their life stages is significantly enhanced by mimicry. A Viceroy egg resembles a tiny plant gall. Both larva and pupa bear a striking resemblance to bird droppings. And the similarity of a Viceroy to a Monarch is well known. For years it was thought that this mimicry was Batesian in nature – a harmless organism (Viceroy) mimicking a poisonous (Monarch) or harmful one in order to avoid a mutual predator. However, recently it’s been discovered that the Viceroy butterfly is as unpalatable as the Monarch, which means that mimicry in its adult stage is technically Mullerian – both organisms are unpalatable/noxious and have similar warning mechanisms, such as the adult butterfly’s coloring.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

July 22, 2019 | Categories: Batesian mimicry, Butterflies, July, Mimicry, Monarch Butterfly, Mullerian Mimicry, Uncategorized, Viceroy Butterfly | Tags: Limenitis archippus | 5 Comments

Mimicry, warning coloration and camouflage are three of the many ways in which animals have adapted in order to survive.

Mimicry, warning coloration and camouflage are three of the many ways in which animals have adapted in order to survive.

Mimicry, when an animal looks or acts like another organism, is illustrated by the Viceroy butterfly which looks remarkably like a Monarch. Warning coloration often makes predators aware of an organism’s toxicity – Red Efts are a prime example. Camouflage, or cryptic coloration, where an animal resembles its surroundings in coloration, form or movement, is exemplified by Eastern Screech-Owls. Not only is their color pattern that of tree bark, but they often stretch upwards and freeze in an upright position, closing their eyes to prevent reflection in their eyes from announcing their presence to predators or prey.

Eastern Screech-Owls come in three color morphs, rufous (https://naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com/2019/01/07/eastern-screech-owls-basking/) gray, and (rarely) brown. (Thanks to Marc Beerman and Howard Muscott for photo op.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

February 1, 2019 | Categories: Cryptic Coloration, Eastern Screech-Owl, Eastern Screech-Owl, gray morph, February, Mimicry, Uncategorized, Warning Coloration | Tags: Megascops asio | 9 Comments

To clarify yesterday’s post on mimicry, here are the Viceroy and Monarch, side by side. Note the horizontal black line across the hindwings of the Viceroy. The (larger) Monarch lacks this line.

To clarify yesterday’s post on mimicry, here are the Viceroy and Monarch, side by side. Note the horizontal black line across the hindwings of the Viceroy. The (larger) Monarch lacks this line.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

August 18, 2018 | Categories: August, Mimicry, Monarch Butterfly, Mullerian Mimicry, Uncategorized, Viceroy Butterfly | 12 Comments

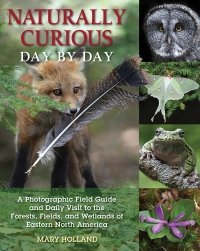

If you’re looking for a present for someone that will be used year round, year after year, Naturally Curious may just fit the bill. A relative, a friend, your child’s school teacher – it’s the gift that keeps on giving to both young and old!

One reader wrote, “This is a unique book as far as I know. I have several naturalists’ books covering Vermont and the Northeast, and have seen nothing of this breadth, covered to this depth. So much interesting information about birds, amphibians, mammals, insects, plants. This would be useful to those in the mid-Atlantic, New York, and even wider geographic regions. The author gives a month-by-month look at what’s going on in the natural world, and so much of the information would simply be moved forward or back a month in other regions, but would still be relevant because of the wide overlap of species. Very readable. Couldn’t put it down. I consider myself pretty knowledgeable about the natural world, but there was much that was new to me in this book. I would have loved to have this to use as a text when I was teaching. Suitable for a wide range of ages.”

In a recent email to me a parent wrote, “Naturally Curious is our five year old’s unqualified f-a-v-o-r-I-t-e book. He spends hours regularly returning to it to study it’s vivid pictures and have us read to him about all the different creatures. It is a ‘must have’ for any family with children living in New England…or for anyone that simply shares a love of the outdoors.”

I am a firm believer in fostering a love of nature in young children – the younger the better — but I admit that when I wrote Naturally Curious, I was writing it with adults in mind. It delights me no end to know that children don’t even need a grown-up middleman to enjoy it!

November 23, 2012 | Categories: A Closer Look at New England, Adaptations, Amphibians, Animal Adaptations, Animal Architecture, Animal Communication, Animal Diets, Animal Eyes, Animal Signs, Animal Tracks, Anti-predatory Device, Ants, April, Arachnids, Arthropods, August, Bark, Bats, Beavers, Beetles, Bird Diets, Bird Nests, Bird Songs, Birds, Birds of Prey, Black Bears, Bogs, Bugs, Bumblebees, Butterflies, camouflage, Carnivores, Carnivorous Plants, Caterpillars, Cervids, Chrysalises, Cocoons, Conifers, Courtship, Crickets, Crustaceans, Damselflies, December, Deciduous Trees, Decomposition, Deer, Defense Mechanisms, Diets, Diptera, Dragonflies, Ducks, Earwigs, Egg laying, Ephemerals, Evergreen Plants, Falcons, Feathers, February, Fishers, Fledging, Fledglings, Flies, Flowering Plants, Flying Squirrels, Food Chain, Foxes, Frogs, Fruits, Fungus, Galls, Gastropods, Gills, Grasshoppers, Gray Foxes, Herbivores, Herons, Hibernation, Honeybees, Hornets, Hymenoptera, Insect Eggs, Insect Signs, Insects, Insects Active in Winter, Invertebrates, January, July, June, Lady's Slippers, Larvae, Leaves, Lepidoptera, Lichens, Mammals, March, Metamorphosis, Micorrhiza, Migration, Millipedes, Mimicry, Molts, Moose, Moths, Mushrooms, Muskrats, Mutualism, Nests, Nocturnal Animals, Non-flowering plants, North American River Otter, November, October, Odonata, Omnivores, Orchids, Owls, Parasites, Parasitic Plants, Passerines, Plants, Plumage, Poisonous Plants, Pollination, Porcupines, Predator-Prey, Pupae, Raptors, Red Foxes, Red Squirrel, Reptiles, Rodents, Scat, Scent Marking, Seed Dispersal, Seeds, Senses, September, Sexual Dimorphism, Shorebirds, Shrubs, Slugs, Snails, Snakes, Snowfleas, Social Insects, Spiders, Spores, Spring Wildflowers, Squirrels, Striped Skunks, Toads, Tracks, Tree Buds, Tree Flowers, Tree Identification, Trees, Trees and Shrubs, turtles, Vernal Pools, Vertebrates, Vines, Wading Birds, Warblers, Wasps, Waterfowl, Weasel Family, White-tailed Deer, Winter Adaptations, Woodpeckers, Woody Plants, Yellowjackets, Young Animals | Tags: Christmas Gifts, Naturally Curious, Naturally Curious by Mary Holland | 2 Comments

The Giant Swallowtail (Papilio crestphones) appears to be extending its range northward into Vermont. It was first confirmed here two years ago, and more sightings have been made each summer since then. The Giant Swallowtail is the largest butterfly in North America, with roughly a 4-6-inch wingspan. Because of the caterpillar’s preference for plants in the citrus family, this butterfly is generally is found further south. However, Prickly Ash (Zanthoxylum americanum) is found in northern New England, and it is a member of the citrus family. With this food source, and increasingly warm winters, the Giant Swallowtail may be here to stay. The larval stage, or caterpillar, is as, or more, impressive as the adult butterfly. Its defense mechanisms have to be seen to be believed. The caterpillar looks exactly like a bird dropping (it even appears shiny and wet), making it appear unpalatable to most insect-eaters. As if that weren’t enough, when and if it is threatened, a bright red, forked structure called an osmeterium emerges from its “forehead” and a very distinctive and apparently repelling odor to insect-eaters, is emitted.

The Giant Swallowtail (Papilio crestphones) appears to be extending its range northward into Vermont. It was first confirmed here two years ago, and more sightings have been made each summer since then. The Giant Swallowtail is the largest butterfly in North America, with roughly a 4-6-inch wingspan. Because of the caterpillar’s preference for plants in the citrus family, this butterfly is generally is found further south. However, Prickly Ash (Zanthoxylum americanum) is found in northern New England, and it is a member of the citrus family. With this food source, and increasingly warm winters, the Giant Swallowtail may be here to stay. The larval stage, or caterpillar, is as, or more, impressive as the adult butterfly. Its defense mechanisms have to be seen to be believed. The caterpillar looks exactly like a bird dropping (it even appears shiny and wet), making it appear unpalatable to most insect-eaters. As if that weren’t enough, when and if it is threatened, a bright red, forked structure called an osmeterium emerges from its “forehead” and a very distinctive and apparently repelling odor to insect-eaters, is emitted.

September 8, 2012 | Categories: Adaptations, Arthropods, Butterflies, Caterpillars, Defense Mechanisms, Insects, Invertebrates, Larvae, Lepidoptera, Metamorphosis, Mimicry | Tags: Giant Swallowtail, Papilio, Papilio crestphones, Prickly Ash, Swallowtail Butterflies, Zanthoxylum americanum | 3 Comments

The Viceroy Butterfly closely resembles the Monarch Butterfly, but is smaller, and has a black line that runs across the veins of its back wings, which the Monarch lacks. While Viceroys don’t contain the poisonous cardiac glycosides that Monarchs do, they do contain salicylic acid due to fact that the larvae feed on willows. This acid not only causes the Viceroy to taste bad, but makes whatever eats it sick. So not only do these two butterflies look alike, but they discourage predators in the same way. This is not a coincidence. The fact that they are both toxic if eaten and are preyed upon by some of the same predators has led to their similar appearance. This phenomenon is referred to as Müllerian mimicry, and essentially it means if two insects resemble each other, they both benefit from each other’s defense mechanism — should a predator eat one insect with a certain coloration and find it inedible, it will learn to avoid catching any insects with similar coloration.

The Viceroy Butterfly closely resembles the Monarch Butterfly, but is smaller, and has a black line that runs across the veins of its back wings, which the Monarch lacks. While Viceroys don’t contain the poisonous cardiac glycosides that Monarchs do, they do contain salicylic acid due to fact that the larvae feed on willows. This acid not only causes the Viceroy to taste bad, but makes whatever eats it sick. So not only do these two butterflies look alike, but they discourage predators in the same way. This is not a coincidence. The fact that they are both toxic if eaten and are preyed upon by some of the same predators has led to their similar appearance. This phenomenon is referred to as Müllerian mimicry, and essentially it means if two insects resemble each other, they both benefit from each other’s defense mechanism — should a predator eat one insect with a certain coloration and find it inedible, it will learn to avoid catching any insects with similar coloration.

July 30, 2012 | Categories: Adaptations, Arthropods, Butterflies, Defense Mechanisms, Insects, Invertebrates, July, Lepidoptera, Mimicry | Tags: Danaus, Danaus plexippus, Defense Mechanisms, Limenitis archippus, Liminitis, Mimicry, Monarch, Monarch Butterfly, Mullerian Mimicry, Nymphalidiae, Viceroy, Viceroy Butterfly | 1 Comment

Congratulations to Sharon Weizenbaum, Beth Herr and David Ascher for correctly identifying the Mystery Photo as the tip of the abdomen of a Common Walkingstick (Diapheromera femorata), also known as Devil’s Darning Needle, Devil’s/Witch’s Riding Horse, and Prairie Alligator due to its unusual shape. While the Common Walkingstick is a mere 3” long, the largest North American species can grow to 7” and one tropical species may reach 14”.

Congratulations to Sharon Weizenbaum, Beth Herr and David Ascher for correctly identifying the Mystery Photo as the tip of the abdomen of a Common Walkingstick (Diapheromera femorata), also known as Devil’s Darning Needle, Devil’s/Witch’s Riding Horse, and Prairie Alligator due to its unusual shape. While the Common Walkingstick is a mere 3” long, the largest North American species can grow to 7” and one tropical species may reach 14”.

Mimicry, warning coloration and camouflage are three of the many ways in which animals have adapted in order to survive.

Mimicry, warning coloration and camouflage are three of the many ways in which animals have adapted in order to survive.  To clarify yesterday’s post on mimicry, here are the Viceroy and Monarch, side by side. Note the horizontal black line across the hindwings of the Viceroy. The (larger) Monarch lacks this line.

To clarify yesterday’s post on mimicry, here are the Viceroy and Monarch, side by side. Note the horizontal black line across the hindwings of the Viceroy. The (larger) Monarch lacks this line. The Viceroy Butterfly closely resembles the Monarch Butterfly, but is smaller, and has a black line that runs across the veins of its back wings, which the Monarch lacks. While Viceroys don’t contain the poisonous cardiac glycosides that Monarchs do, they do contain salicylic acid due to fact that the larvae feed on willows. This acid not only causes the Viceroy to taste bad, but makes whatever eats it sick. So not only do these two butterflies look alike, but they discourage predators in the same way. This is not a coincidence. The fact that they are both toxic if eaten and are preyed upon by some of the same predators has led to their similar appearance. This phenomenon is referred to as Müllerian mimicry, and essentially it means if two insects resemble each other, they both benefit from each other’s defense mechanism — should a predator eat one insect with a certain coloration and find it inedible, it will learn to avoid catching any insects with similar coloration.

The Viceroy Butterfly closely resembles the Monarch Butterfly, but is smaller, and has a black line that runs across the veins of its back wings, which the Monarch lacks. While Viceroys don’t contain the poisonous cardiac glycosides that Monarchs do, they do contain salicylic acid due to fact that the larvae feed on willows. This acid not only causes the Viceroy to taste bad, but makes whatever eats it sick. So not only do these two butterflies look alike, but they discourage predators in the same way. This is not a coincidence. The fact that they are both toxic if eaten and are preyed upon by some of the same predators has led to their similar appearance. This phenomenon is referred to as Müllerian mimicry, and essentially it means if two insects resemble each other, they both benefit from each other’s defense mechanism — should a predator eat one insect with a certain coloration and find it inedible, it will learn to avoid catching any insects with similar coloration.

What Other Naturally Curious People Are Saying