Snapping Turtle Eggs Hatching

For the past three months, Snapping Turtle eggs have been buried roughly five to ten inches deep in sandy soil (depth depends on the size of the female laying them), absorbing heat from the sun-warmed soil. Come September, the relatively few Snapping Turtle eggs that have avoided predation are hatching. The sex of the baby turtles correlates to the temperature of the clutch. Temperatures of 73-80 °F will produce males, slightly above and below will produce both sexes, and more extreme temperatures will produce females. The miniature snappers crawl their way up through the earth and head for the nearest pond, probably the most perilous journey of their lives.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Snapping Turtle Seeking Sandy Soil In Which To Lay Eggs

Monday’s Mystery Photo leaves no doubt that Naturally Curious readers are among the most informed nature interpreters out there. There were many correct answers, but congratulations go to Susan Cloutier, who was the first to identify the tracks and diagnostic wavy line left by the tail of a female Snapping Turtle as she traveled overland seeking sandy soil in which to lay her eggs. The turtle eventually found a suitable spot, dug several holes and chose one in which to deposit her roughly 30 eggs, covered them with soil and immediately headed back to her pond, leaving her young to fend for themselves if and when they survive to hatch in the fall.

Unfortunately, there is little guarantee that the eggs will survive. Skunks (the main predators), raccoons, foxes and mink have all been known to dig turtle eggs up within the first 24 hours of their being laid and eat them, leaving tell-tale scattered shells exposed on the ground. Fortunately, Snapping Turtles live at least 47 years, giving them multiple chances to have at least one successful nesting season. (Thanks to Chiho Kaneko and Jeffrey Hamelman for photo op.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Snapping Turtle Eggs Hatching

Every fall, roughly three months after they’re laid, snapping turtle eggs hatch. Like many other turtle species, the hatchlings’ gender is determined by the temperature at which the eggs were incubated during the summer. Eggs at the top of the nest are often significantly warmer than those at the bottom, resulting in all females from the top eggs, and all males from the bottom eggs. In some locations, the hatchlings emerge from the nest in hours or days, and in others, primarily in locations warmer than northern New England, they remain in the nest through the winter.

Every fall, roughly three months after they’re laid, snapping turtle eggs hatch. Like many other turtle species, the hatchlings’ gender is determined by the temperature at which the eggs were incubated during the summer. Eggs at the top of the nest are often significantly warmer than those at the bottom, resulting in all females from the top eggs, and all males from the bottom eggs. In some locations, the hatchlings emerge from the nest in hours or days, and in others, primarily in locations warmer than northern New England, they remain in the nest through the winter.

When they emerge above ground, the hatchlings, without any adult guidance, make their way to the nearest body of water, which can be up to a quarter of a mile away, and once there, seek shallow water. Eggs and snapping turtle hatchlings are extremely vulnerable to predation. Predators include, among others, larger turtles, great blue herons, crows, raccoons, skunks, foxes, bullfrogs, water snakes, and large predatory fish, such as largemouth bass. Older and larger snapping turtles have a much easier time fending for themselves. (Photo: newborn snapper)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button. (NB: The “Donate” button on the Naturally Curious blog is currently not working. If you would like to donate to the sustainability of this blog, you may send a check made out to Mary Holland to me at 505 Wake Robin Drive, Shelburne, VT 05482.)

Snapping Turtles’ Extensive Reach

When you see a Snapping Turtle on land, its head is often only a few inches out of its shell, but don’t be fooled! The length of its neck can be up to two-thirds the length of its shell and if threatened it can quickly extend its neck all the way out. (Keeping yourself out of reach is wise. However, come June, when female Snapping Turtles often are found crossing roads when they leave their ponds to lay eggs, rescuing them from oncoming cars usually calls for close proximity to them. To hold and transport them (to the side of the road they were headed), just grab the back end of the shell, where their head can’t quite reach your hands.)

When you see a Snapping Turtle on land, its head is often only a few inches out of its shell, but don’t be fooled! The length of its neck can be up to two-thirds the length of its shell and if threatened it can quickly extend its neck all the way out. (Keeping yourself out of reach is wise. However, come June, when female Snapping Turtles often are found crossing roads when they leave their ponds to lay eggs, rescuing them from oncoming cars usually calls for close proximity to them. To hold and transport them (to the side of the road they were headed), just grab the back end of the shell, where their head can’t quite reach your hands.)

Their long neck allows Snapping Turtles to capture prey such as fish, frogs and crayfish from a distance. When in shallow water, they can lie on the muddy bottom of the pond with only their heads occasionally exposed in order to take an occasional breath. If you look closely at a Snapping Turtle’s head (see photo), you will see that their nostrils are positioned on the very tip of their snout, effectively functioning as snorkels.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

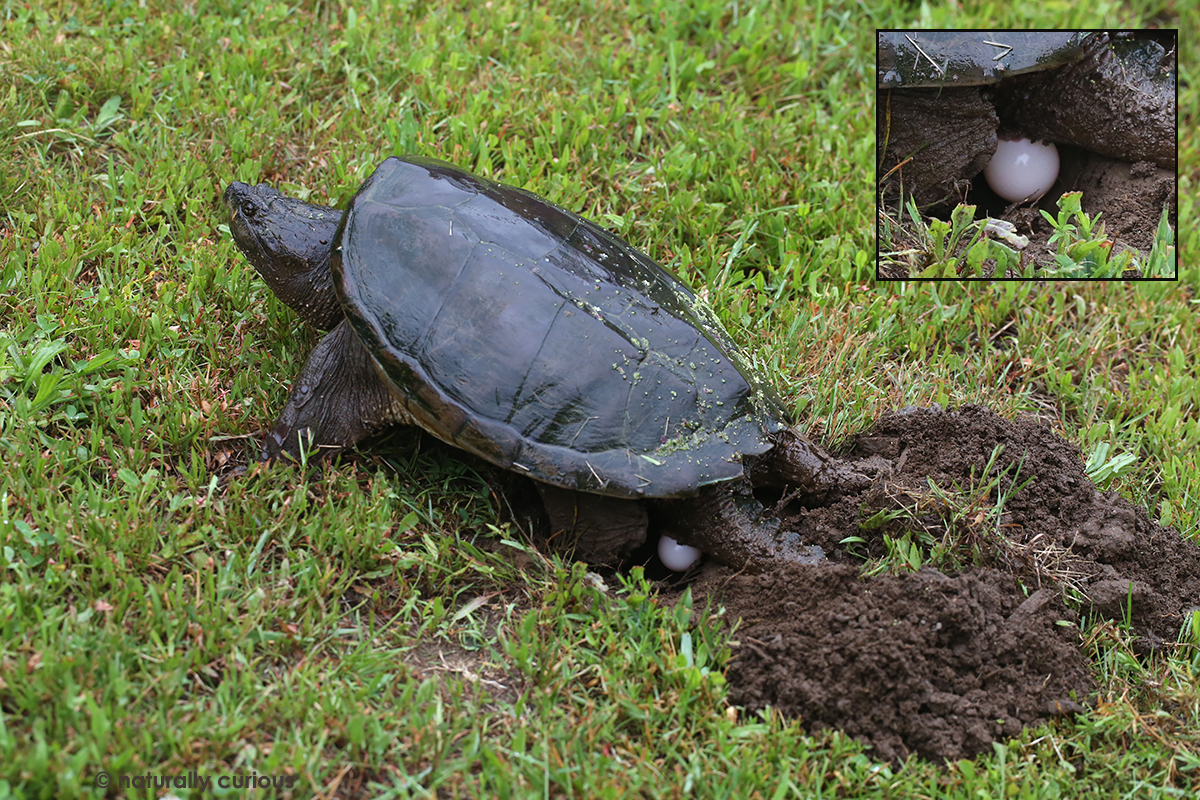

Snapping Turtles Laying Eggs – Sex Of Turtles Determined By Temperature

It’s that time of year again, when female Snapping Turtles are leaving ponds, digging holes in sandy soil and depositing up to 80 eggs (20-30 is typical) before covering them up and returning to their ponds. While the sex of most snakes and lizards is determined by sex chromosomes at the time of fertilization, the sex of most turtles is determined by the environment after fertilization. In these reptiles, the temperature of the eggs during a certain period of development is the deciding factor in determining sex, and small changes in temperature can cause dramatic changes in the sex ratio.

It’s that time of year again, when female Snapping Turtles are leaving ponds, digging holes in sandy soil and depositing up to 80 eggs (20-30 is typical) before covering them up and returning to their ponds. While the sex of most snakes and lizards is determined by sex chromosomes at the time of fertilization, the sex of most turtles is determined by the environment after fertilization. In these reptiles, the temperature of the eggs during a certain period of development is the deciding factor in determining sex, and small changes in temperature can cause dramatic changes in the sex ratio.

Often, eggs incubated at low temperatures (72°F – 80°F) produce one sex, whereas eggs incubated at higher temperatures (86°F and above) produce the other. There is only a small range of temperatures that permits both males and females to hatch from the same brood of eggs. The eggs of the Snapping Turtle become female at either cool (72°F or lower) or hot (82°F or above) temperatures. Between these extremes, males predominate. (Developmental Biology by S. Gilbert)

If the cool temperatures we’ve experienced thus far this spring continue, there could be a lot of female Snapping Turtles climbing up out of the earth come September. (Thanks to Clyde Jenne and Jeffrey Hamelman for photo opportunity)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Snapping Turtles Emerging From Hibernation

Congratulations to Elizabeth Hall, the first reader to correctly identify the trail blazer in the previous NC post!

Congratulations to Elizabeth Hall, the first reader to correctly identify the trail blazer in the previous NC post!

As you can see from the dirt piled on this Snapping Turtle’s head, it has just emerged from hibernation. After extracting themselves from their muddy hibernacula, Snapping Turtles have two missions: to raise their body temperature and to secure food. According to Jim Andrews, Director of the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas (https://www.vtherpatlas.org/ ), the first movement of the year for these turtles is often to seek shallow water where they can bask in the sun and heat their internal organs. They also are on the move in order to get from their overwintering site (shallows of ponds, marshes, and lakeshores, in a spring or a stream) back to a feeding area. It won’t be long before they will be searching for mates.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Snapping Turtles Entering Hibernation

Most Snapping Turtles have entered hibernation by late October. To hibernate, they burrow into the debris or mud bottom of ponds or lakes, settle beneath logs, or retreat into muskrat burrows or lodges. Once a pond is frozen over, how do they breathe with ice preventing them from coming up for air?

Most Snapping Turtles have entered hibernation by late October. To hibernate, they burrow into the debris or mud bottom of ponds or lakes, settle beneath logs, or retreat into muskrat burrows or lodges. Once a pond is frozen over, how do they breathe with ice preventing them from coming up for air?

Because turtles are ectotherms, or cold-blooded, their body temperature is the same as their surroundings. The water at the bottom of a pond is usually only a few degrees above freezing. Fortunately, a cold turtle in cold water/mud has a slow metabolism. The colder it gets, the slower its metabolism, which means there is less and less of a demand for energy and oxygen as temperatures fall – but there is still some.

When hibernating, Snapping Turtles rely on stored energy. They acquire oxygen from pond water moving across the surface of their body, which is highly vascularized. Blood vessels are particularly concentrated near the turtle’s tail, allowing the Snapper to obtain the necessary amount of oxygen to stay alive without using its lungs.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to https://naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Common Loon Chicks Hatching

Newly-hatched Common Loon chicks can swim as soon as they hit the water, which they do as soon as their down dries after hatching, usually within 24 hours. Their buoyancy and lack of maneuverability, however, leave them vulnerable to predators. Parents usually don’t stray far from their young chicks due to the omnipresent threat of eagles, hawks, gulls, large fish and snapping turtles. During their first two weeks, young loon chicks often seek shelter (and rest) on the backs of their parents.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to https://naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Mystery Photo I.D. – Leeches feeding on the blood of a Snapping Turtle

Leeches are segmented worms (annnelids) which feed predominantly on blood, although some species do eat insects. Of the 700 species of leeches, 500 inhabit fresh water, as opposed to salt water or land. Blood-sucking leeches are common parasites of many freshwater vertebrates including turtles, amphibians and fish.

Leeches are segmented worms (annnelids) which feed predominantly on blood, although some species do eat insects. Of the 700 species of leeches, 500 inhabit fresh water, as opposed to salt water or land. Blood-sucking leeches are common parasites of many freshwater vertebrates including turtles, amphibians and fish.

Generally speaking, leeches of the genus Placobdella are commonly found on turtles. Bottom-dwelling species such as the Common Snapping Turtle, Mud Turtle and Musk Turtle usually have more leeches than other turtles, and they are often attached to the skin at the limb sockets. Aerially-basking species such as Painted Turtles often have fewer of these parasites, possibly because basking forces leeches to detach in order to avoid desiccation.

A leech can ingest several times its weight in blood from one host before dropping off and not feeding again for weeks, or even months. Leeches inject hirudin, an anesthetic, to keep the hosts from feeling them break the skin. They also inject an anticoagulant to keep the blood from clotting so that they can feed. Although leeches (especially large ones) can be a significant health detriment to smaller animals, they are not harmful to most large animals, such as Snapping Turtles.

Some of the most common predators of leeches include turtles, fish, ducks, and other birds. Map Turtles allow Common Grackles to land in basking areas and peck at leeches clinging to their skin, and minnows have been seen cleaning leeches from Wood Turtles in the water. At times turtles bury themselves in ant mounds to rid themselves of these pesky parasites.

For those readers who may hesitate before going into a leech-laden pond, it may be comforting to know that leeches are mainly nocturnal. (Photo by Jeannie Killam)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Snapping Turtle Nests Raided

Female Snapping Turtles spend a lot of time and effort finding suitable sandy soil in which to dig their nest and lay their eggs. Some turtles have been found laying their eggs as far as a mile from the nearest water source. Once she has laid her eggs and covered them with soil, the female snapper returns to her pond, leaving her eggs to hatch on their own, and the hatchlings to fend for themselves.

Female Snapping Turtles spend a lot of time and effort finding suitable sandy soil in which to dig their nest and lay their eggs. Some turtles have been found laying their eggs as far as a mile from the nearest water source. Once she has laid her eggs and covered them with soil, the female snapper returns to her pond, leaving her eggs to hatch on their own, and the hatchlings to fend for themselves.

It is estimated that as many as 80 to 90 percent of all turtle nests are destroyed by predators, weather conditions and accidental disturbances. Most of the damage is done by predators – skunks, raccoons, foxes, crows, among others. Most nests are discovered by smell, and most are raided at night. The fluid that coats the eggs, that is lost by the mother during egg laying or is lost through breaks in the eggs, produces a smell that is easily detected by predators. While a majority of nest raids happen within the first 48 hours of the eggs being laid, studies have shown that predation occurs over the entire incubation period (June – September). The pictured Snapping Turtle nest was dug up and the eggs consumed 10 days after they were laid.

If you are aware of a spot where a turtle dug a nest and laid eggs, you can try to protect the nest from predators by placing either a bottomless wire cage or an oven rack over the nest site, and putting a heavy rock on top. The tiny hatchlings will be able to escape through the openings but hopefully, if the rock is heavy enough, raccoons and skunks will become discouraged and give up trying to reach the nest.

The next Naturally Curious post will be on 7/5/17.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Snapping Turtles Laying Eggs

In June, mature female Snapping Turtles leave their ponds in search of a sandy spot in which to lay their eggs. (Capable of storing viable sperm for up to three years, female snappers do not necessarily mate every year prior to laying eggs.) Once this prehistoric-looking reptile locates a suitable location she slowly scoops one footful of earth at a time up and to the rear of her, alternating her left and right hind feet. If the soil is dry and tightly packed, she will urinate on it in order to facilitate digging.

In June, mature female Snapping Turtles leave their ponds in search of a sandy spot in which to lay their eggs. (Capable of storing viable sperm for up to three years, female snappers do not necessarily mate every year prior to laying eggs.) Once this prehistoric-looking reptile locates a suitable location she slowly scoops one footful of earth at a time up and to the rear of her, alternating her left and right hind feet. If the soil is dry and tightly packed, she will urinate on it in order to facilitate digging.

Hole made, she proceeds to slowly lift her body and release ping pong ball-sized, -colored and -shaped eggs, usually one at a time, but occasionally two, into the hole beneath her. Down she comes for a minute or two of rest, and then up she rises again to release another egg. She does this anywhere from 20 to 40 times, a process that can take up to several hours, depending on the number of eggs she lays. Then her large, clawed hind feet slowly begin to scrape the two piles of soil she removed back into the hole, one foot at a time, until the eggs are covered, at which point she tamps the soil down with her plastron, or bottom shell. She then returns to the water, leaving the eggs and hatchlings to fend for themselves.

It is hard to accept that after all the effort that has been put into this act, studies have shown that 90 percent or more of turtle nests are raided by the likes of raccoons, skunks and crows. For those nests that are not discovered by predators, the sex of the turtle that emerges from each egg is determined by the temperature it attained during a specific part of its development. Eggs maintained during this period at 68°F produce only females; eggs maintained at 70-72°F produce both male and female turtles, and those incubated at 73-75°F produce only males. The eggs hatch in September, with many of the Snapping Turtles emerging then, but in the northern part of their range, young Snapping Turtles sometimes overwinter in their nest and emerge in the spring. (Thanks to Chiho Kaneko and Jeffrey Hamelman for photo op.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Snapping Turtle Takes Advantage of Opportunity to Breathe Air

Opportunities to see turtles in winter are extremely limited, but a hole chopped in pond ice recently revealed a Snapping Turtle swimming in the water beneath the ice. According to Jim Andrews, Director of the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas(http://vtherpatlas.org/ ), most turtles don’t often burrow into the mud during winter. They need to take in dissolved oxygen from the water and there is not much available in the mud. Turtles take in oxygen through the linings of their mouths and sometimes thin-skinned, capillary-rich areas in their cloaca and armpits. Many turtles are just sitting on the bottom of ponds. They may use a rock, log, or maybe some leaves for a little protection from otters or other predators.

Opportunities to see turtles in winter are extremely limited, but a hole chopped in pond ice recently revealed a Snapping Turtle swimming in the water beneath the ice. According to Jim Andrews, Director of the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas(http://vtherpatlas.org/ ), most turtles don’t often burrow into the mud during winter. They need to take in dissolved oxygen from the water and there is not much available in the mud. Turtles take in oxygen through the linings of their mouths and sometimes thin-skinned, capillary-rich areas in their cloaca and armpits. Many turtles are just sitting on the bottom of ponds. They may use a rock, log, or maybe some leaves for a little protection from otters or other predators.

If the ice is clear, it is possible to see turtles swimming beneath it. Andrews suggests that the Snapping Turtle in the photograph is likely picking up an oxygen boost by using its lungs for a change. It may be four more months before it gets another breath of fresh air. (Thanks to Jim Andrews for post and Barb and Paul Kivlin of Shoreham, VT for photo.)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Snapping Turtles & Duckweed

Duckweed (Wolfia sp.), a free-floating aquatic plant that possesses flowers which are said to be the smallest flowers in the world, is coating our mystery creature. The presence of this plant can indicate that there are too many nutrients in the water, especially nitrate and phosphate. On the plus side, Duckweed provides waterfowl, juvenile fish and other wildlife (including humans in Southeast Asia) with a protein-rich (40%) food.

Duckweed (Wolfia sp.), a free-floating aquatic plant that possesses flowers which are said to be the smallest flowers in the world, is coating our mystery creature. The presence of this plant can indicate that there are too many nutrients in the water, especially nitrate and phosphate. On the plus side, Duckweed provides waterfowl, juvenile fish and other wildlife (including humans in Southeast Asia) with a protein-rich (40%) food.

Under this green coating is a Snapping Turtle, one of the largest freshwater turtles in North America. Most often encountered in June, when females leave their ponds to lay eggs, Snapping Turtles are infrequently observed at other times of the year. This is primarily due to their crepuscular and nocturnal habits as well as their tendency to spend a lot of time under water feeding on plants, insects, fish, frogs, small turtles, young waterfowl, and crayfish.

Found in most ponds, marshes, streams and rivers, Snapping Turtles are not aggressive towards humans. Their size is impressive (a full-grown Snapping Turtle’s top shell, or carapace, can measure up to 20 inches in length) but they shy away from human disturbance. Miniature versions with one-inch long carapaces can be seen this month as the young Snappers crawl up out of their subterranean nests after hatching from eggs laid in June and head for the nearest water.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go tohttp://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Snapping Turtles Mating

Although Snapping Turtles may mate any time between April and November, much breeding activity takes place during April and May. Snapping Turtle mating appears fairly aggressive, with the male chasing the female, grasping the posterior end of her carapace and then mounting her. He holds on to the edges of her shell with all four legs, often biting her head and neck while he inseminates her.

The female Snapping Turtle can keep sperm viable in her body for several months (and perhaps years). Thus, there can be multiple paternity in egg clutches and it may even be possible that a female’s eggs are fertilized in years when she does not mate. (Thanks to Jim Block for photo. To see a photo series of Snapping Turtles mating (and many other very fine nature photographs), go to http://www.jimblockphoto.com/2010/04/snapping-turtles/)

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

Snapping Turtle Eggs Hatching

Every fall, roughly 3 months after they’re laid, snapping turtle eggs hatch. The hatchlings’ gender is determined by the temperature at which they were incubated during the summer. Eggs at the top of the nest are often significantly warmer than those at the bottom, resulting in all females from the top eggs, and all male from the bottom eggs. In some locations, the hatchlings emerge from the nest in hours or days, and in others, primarily in locations warmer than northern New England, they remain in the nest through the winter. When they emerge above ground, the hatchlings, without any adult guidance, make their way to the nearest body of water, which can be up to a quarter of a mile away, and once there, seek shallow water.

Every fall, roughly 3 months after they’re laid, snapping turtle eggs hatch. The hatchlings’ gender is determined by the temperature at which they were incubated during the summer. Eggs at the top of the nest are often significantly warmer than those at the bottom, resulting in all females from the top eggs, and all male from the bottom eggs. In some locations, the hatchlings emerge from the nest in hours or days, and in others, primarily in locations warmer than northern New England, they remain in the nest through the winter. When they emerge above ground, the hatchlings, without any adult guidance, make their way to the nearest body of water, which can be up to a quarter of a mile away, and once there, seek shallow water.

Naturally Curious is supported by donations. If you choose to contribute, you may go to http://www.naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com and click on the yellow “donate” button.

What Other Naturally Curious People Are Saying